Camp museum honours victims of the past

A former political prisoner camp near the town of Chusovoi in the Urals (southern Russia) is being renovated; the barracks were re-roofed and the fences and watchtowers were painted. After that, the camp was closed for the winter because no tourists will visit it before the spring.

A former political prisoner camp near the town of Chusovoi in the Urals (southern Russia) is being renovated; the barracks were re-roofed and the fences and watchtowers were painted. After that, the camp was closed for the winter because no tourists will visit it before the spring.

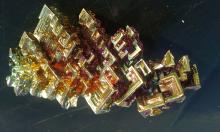

The former Perm-36 prison camp is now a museum. On the outskirts of the remote Kuchino village, the museum is one of the most mysterious psychological phenomena in modern Russia. Why should barbed wire, wards, cells, barracks, camp uniforms with numbers and terrible inscriptions on the walls be preserved? Why not raze to the ground the former camp VS 389/36, Russia's last prison for dissidents?

After the events in Prague in 1969, the Politburo of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union was seized with fear and converted Perm-36 into a prison camp for political dissidents in July 1972. All political prisoners of the country were taken to the camp to be kept there in utmost severity. The prisoners experienced the most barbaric methods of imprisonment. Each prisoner had three security guards. Cells were locked 24 hours a day. Three people could barely walk in the two square metre yard. In addition, there were iron bars on the inside and the outside was covered with electrified barbed wire. A weak person was doomed to a slow death in the camp.

Prisoners were poorly fed and could not receive a package (up to 5 kg) before they served half of their sentence. The minimum sentence was ten years.

Former State Duma Deputy Sergei Kovalyov and editor in chief of the Moskva literary journal, Leonid Borodin are among the camp's most famous prisoners. The camp held political prisoners for 15 years. In December 1987, Gorbachev's glasnost ended the persecution of "dissidence" and the Perm-36 camp closed. Local peasants raided the camp to repair their houses and greenhouses.

However, reflection on hardships is typical of the Russian national character and several years after the camp closed, former prisoners who were now part of the new leadership were alarmed that "their camp" was on the verge of disappearing. Local authorities, Moscow and several western funds sponsored the restoration of the camp at the height of nation-wide chaos and financial troubles. The success of their efforts is amazing.

The camp has been almost completely restored. It's name today is the Perm-36 Memorial Museum of the History of Political Repression of Totalitarianism. It has a small number staff and guides. The few tourists that visit the camp are curious Europeans, journalists and diplomats, like US Ambassador to Russia Alexander Vershbow.

Last autumn an exposition recreating the hell of the prison camp was held in Moscow. A restored prison yard was at the beginning of the exhibit. Opening the exposition, Sergei Kovalyov cut the red ribbon and said jokingly, "I wonder if I am a man or an exhibit here".

The phenomenon of the restored camp and careful preservation of the objects of violence shows that Russia still craves suffering. Russia's national character has always valued wounds.

It is hard to imagine the French restoring a guillotine in la Place de la Concorde to commemorate the terror of the Great French Revolution.

The situation in Russia is quite different. Crucified Christ has always been more important there than Christ ascended or entering Jerusalem full of joy. If Christianity is compared to Christ's body, Russia's mystic place will be on the Saviour's bleeding thigh hit by a soldier's lance.

Anatoly Korolev, RIAN

Subscribe to Pravda.Ru Telegram channel, Facebook, RSS!