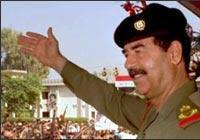

Saddam Hussein declares he ordered trial of Shiites who were executed but insists it was not a crime

A defiant Saddam Hussein admitted in court Wednesday that he ordered the trial of 148 Shiites who were eventually executed in the 1980s, but insisted that doing so was legal because they were suspected in an assassination attempt against him.

"Where is the crime?" Saddam asked, standing before the panel of five judges. "Is referring a defendant who opened fire at a head of state, no matter what his name is, a crime?"

His dramatic courtroom speech came a day after prosecutors in his trial presented a presidential decree with a signature they said was Saddam's approving death sentences for the 148 Shiites, their most direct evidence against him so far in the four-month trial.

Saddam did not admit to signing the approval in his comments.

Saddam and seven co-defendants are on trial for the executions of 148 Shiites, as well as the arrest and torture of others and the confiscation and razing of their farmlands, following a July 8, 1982 attempt to kill the then-Iraqi leader in the town of Dujail .

The prosecution has argued that the crackdown that followed the assassination attempt went far beyond the actual attackers, presenting documents that show entire families were arrested, tortured and held for years, including women and children as young as three months old.

The 148 people eventually sentenced to death in the case included at least 10 juveniles, one as young as 11 years old, according to the documents. The death sentences came after what the prosecution called an "imaginary trial" before Saddam's Revolutionary Court .

But Saddam argued he was acting within the law. He told the court his co-defendants should be freed and that he alone should be tried since he was the president and they were following orders.

"A head of state is here. Try him and let the others go their way," he said.

He pointed to Awad al-Bandar, the former Revolutionary Court whose signature was allegedly on document announcing the death sentences, presented to the court on Tuesday.

"I referred them (the prisoners) to the Revolutionary Court in accordance with the law. Awad implemented the law and was his right to try them," Saddam said.

He referred to the destruction of the Dujail families' farmland, saying: "I razed the land. I razed it, not with bulldozers. It was a resolution issued by the Revolutionary Command Council," a regime instition that Saddam headed.

He said the government had the right to confiscate land for the "national interest" and said he ordered "substantial compensation" be paid to its owners.

Chief judge Raouf Abdel-Rahman was about to adjourn the session when Saddam interrupted him and asked to be allowed to speak. Saddam stood and made the comments in a 15-minute speech, then the judge adjourned the session until March 12.

Over the past two days, the prosecution presented on an overhead screen a series of documents detailing the bureaucracy behind the wave of arrests and executions. Among them was the June 16, 1984 presdidential decree approving the executions.

In often dry government language, the memos, decrees, even handwritten notes from Saddam's presidential office, the Mukhabarat intelligence service headed by his co-defendant Barazan Ibrahim and other agencies laid out a paper trail behind the suffering that prosecution witnesses recounted in the first months of the trial.

Those witnesses Dujail residents told the court in previous sesions that they were imprisoned and tortured and that their relatives were killed. Several women related how they were stripped naked, beaten or given electric shocks one testifying that Ibrahim himself kicked her in the chest as she hung upside down.

On Wednesday, chief prosecutor Jaafar al-Moussawi showed handwritten letters said to be from three of the defendants sent to the Interior Ministry in the days after the assassination attempt on Saddam, informing on Dujail families linked to the Dawa Party, a Shiite opposition militia accused in the attack.

More than 10 of the names in the letters eventually appeared on the list of those sentenced to death, and al-Moussawi said the three men therefore had a direct role in their deaths.

"May my hand be cut off if I gave information against anyone," defendant Ali Dayih, who allegedly wrote one of the letters, said. "I had no political responsiblity ... It's all a frameup."

Two other defendants Abdullah Kazim Ruwayyid and his son Mizhar, who, like Dayih, were allegedly local Dujail officials from Saddam's Baath Party also stood and denied that the letters were theirs.

"The handwriting is not mine. The signature is not mine," Mizhar Ruwayyid said. He insisted his only job in Dujail was as a telephone operator. He argued that the vocabulary used in the letter showed it wasn't his. "I only finished elementary school and the document presented was written by someone with a bachelor's degree," he said.

Saddam also stood to defend the men, saying that "leaving aside the issue of whether these documents were forged," they were simply notifying authorities.

"This was an informing operation, like any policeman when he tells something to his station or any citizen who sees or hears (a crime)," Saddam argued. "To say that those people were sentenced to death because Abdullah wrote or it was said that he wrote it, this is rubbish."

The prosecution detailed how 399 detained men, women and children from Dujail were transported in 1984 from a Baghdad prison to a desert prison in southern Iraq .

For each vehicle that carried the prisoners, a list was made at the time, with the names of the drivers and the prisoners on board. Al-Moussawi presented more than a dozen of the handwritten lists.

Among the names of prisoners was a 3-month-old girl named Suad Jassim, as well as entire families, including women and their pre-teen children.

In contrast to the outbursts, insults and arguments that characterized past proceedings, the defendants listened silently as the documents were shown. When they wanted to make a point, they raised their hands, and Abdel-Rahman often told them to wait, then let them speak later.

Saddam's defense team attended the trial, as they did in Tuesday's session, after ending a boycott even though Abdel-Rahman rejected their demand that he step down.

The turn in the case boosted hopes the controversial trial will be seen as credible in a country still sharply divided by Saddam's legacy.

But those splits have only gotten wider amid a surge of bloody sectarian violence between Iraq 's Sunnis and Shiites. At least 68 people were killed Tuesday in bombings and mortar barrages, mainly against religious targets, in continued violence sparked by an attack last week on a major Shiite shrine, reports the AP.

D.M.

Subscribe to Pravda.Ru Telegram channel, Facebook, RSS!