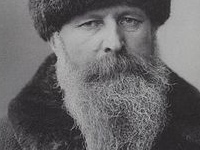

Commemorating Russian painter Vasily Vereshchagin

Vasily Vasilyovich Vereshchagin was born on the 26th of October 1842 in Cherepovets, Novgorod Governate, and died as he had lived, depicting a scene of war. On the 13th of April 1904, during the Russo-Japanese War, the Russian battleship "Petropavlovsk" detonated a Japanese mine just outside of Port Arthur in Russian Manchuria.

by Olivia Kroth

On the 26th of October 2012, Vasily Vasilyovich Vereshchagin would have celebrated his 170th birthday, a Russian painter who created landscapes and portraits, but gained international fame especially for his battle scenes, both contemporary and historical.

He was born on the 26th of October 1842 in Cherepovets, Novgorod Governate, and died as he had lived, depicting a scene of war. On the 13th of April 1904, during the Russo-Japanese War, the Russian battleship "Petropavlovsk" detonated a Japanese mine just outside of Port Arthur in Russian Manchuria.

The ship sank immediately, taking all of the crew down to their wet grave, including Vasily Vasilyovich Vereshchagin. The painter, aged 61, reportedly sat at his easel on deck until the very last moment, in order to finish his work before he drowned.

Vasily Vasilyovich Vereshchagin's whole life appears to be a paradox, as he often professed to abhor wars, yet he participated in several of them and finally died in a war. Looking at his biography, we will notice the contrast between his pronounced pacifism and his active participation in battles.

His father, a landowner of noble birth, sent the boy to Tsarskoe Selo when he was eight years young, to start a military career in the Tsar's Sea Cadet Corps. Vasily Vasilyovich Vereshchagin served on the frigate "Kamchatka," going on his first sea voyage in 1858 at the age of 18.

After graduating from the naval school of Saint Petersburg, he decided to become a painter and joined the Imperial Academy of Arts. His father, who had envisaged a military career for his son, was so enraged that he cut off all financial aid to Vasily.

But the painter was able to sell his artwork very soon, towards midlife he had become wealthy, selling his pictures in Russia and abroad. Today many museums and private art collectors around the globe are proud to own some of his extraordinary paintings.

In 1867, Vasily Vasilyovich Vereshchagin set out for Turkestan at the invitation of General Konstantin Petrovich von Kaufmann, who asked him to accompany him on this expedition to Central Asia.

In 1868, the artist, turned soldier at the age of 28, took part in the Siege of Samarkand. For his patriotic heroism he was later rewarded with the Cross of Saint George, Fourth Class.

General Konstantin Petrovich von Kaufmann (1818-1882) served as first Governor-General of Russian Turkestan. His family stemmed from Austria, but had immigrated to Russia, converted to Orthodoxy and served the Tsars for more than 100 years.

Throughout the 19th century, the Russian Empire was preoccupied with its Southern border. Tsarist policies alternated between extension through annexation of new territories, consolidation and defense. The Southern border, a long landline, reached from the Black Sea in the Southwest to Manchuria on the Japanese Sea in the Southeast.

By the end of the 19th century, the size of the Russian Empire had increased to 22.400.000 square kilometers, comprising one-sixth of the Earth's landmass. The Southern border ran through vast stretches of land with inhabitants of great cultural, ethnic, economic and religious disparity.

General-Governor Konstantin Petrovich von Kaufmann helped to defend and extend the Russian Empire's southern border in Central Asia. In 1867, Turkestan was made a Russian Governor-Generalship, with the capital Tashkent. It consisted of three provinces: Syr Darya, Semirechye Oblast and Samarkand Oblast. Other oblasts were to follow soon, as surrounding land was being annexed.

In his Governate, Von Kaufmann was rather independent from central control, isolated geographically from European Russia by the wide, endless steppe. In those days, it took two months to cross the vast stretches lying between Saint Petersburg and Tashkent. Furthermore, the Russian outpost was isolated in the minds of Tsarist officials who neither understood nor appreciated its ancient Islamic culture.

The young painter, Vasily Vasilyovich Vereshchagin, was fascinated by the steppe and Islamic culture, as his pictures show, but the military action shocked him because of its cruelty. In 1871, he created his famous tableau "Apotheosis of War" as part of a series called "The Barbarians," and dedicated it "to all conquerors, past present and to come."

We see a high mound of human skulls, heaped on the yellow-brownish sand of a Central Asian desert. In the background, some ruins of an empty town have been left, broken walls, a blasted minaret, a ghastly place without a living soul.

Black ravens are circling under a sunny, blue sky. Some of the birds have settled on the skulls, although there is no flesh left to feed upon. The bones have been bleached by the sun, some of the mouths are gaping wide open, as if the dying human beings had yelled in agony.

The Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow, where the picture is on display, gives the following explanation: "The viewer beholds a dead wasteland baked by the sun. In the distance, there is a plundered city, in the centre, a pyramid of human skulls ..."

Then it goes on about the cruelty of Tamerlane's wars, the Mongol Emperor, who a few centuries after Genghis Khan subjugated Asia by means that cannot have been all too soft. Aren't all wars cruel, though? Were Tamerlane's wars crueller than others?

No explanation is given for the term "apotheosis," which sounds puzzling in this context. The Thesaurus dictionary enumerates about two dozen synonyms. They help to make the bewilderment complete: adoration, adulation, deification, exaltation, exemplification, glorification, idolization, laudation, quintessence, representation and so on.

A masterly exemplification and allegoric representation of war they certainly are, these bleached skulls, baking in the sun. An adoration and glorification of war they are certainly not, unless we might suppose that Tamerlane was highly satisfied with having killed so many people that he could build pyramids with their skulls.

The painting teaches us that the Gods of War are merciless, demanding and receiving their bloody tribute, as the term "deification" suggests. The Gods of War must be fed continuously with the sacrifice of human lives, to keep their favors on the victor's side.

Interestingly, Vasily Vasilyovich Vereshchagin was born under the zodiac sign of the Scorpio, whose planet ruler is Mars, the ancient Roman God of War. This could partly explain his innermost drive to follow the paths of the Russian Empire's wars, although he abhorred bloodshed, cruelty and pain.

He wrote in his diary, "Does war have two sides? One that is pleasant and attractive, the other that is ugly and repulsive? No, there is only one war. It attempts to kill, injure or take as many people prisoner as possible. The stronger adversary beats the weaker, until the weaker pleads for mercy."

Little did he know of the wars that were to follow in the future, for example the Great Patriotic War, known worldwide as the Second World War, where tank battles raged and bombs fell from the sky, including two atom bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945, extinguishing thousands of lives. The following generations of Japanese children were born with genetic malfunction and illnesses, such as cancer.

Nor could the painter foresee the horrors of the Vietnam War (1955-1975), when Agent Orange was sprayed from helicopters, killing 400.000 Vietnamese civilians and causing 500.000 Vietnamese children to be born with birth defects.

Vasily Vasilyovich Vereshchagin knew nothing about the ultimate warfare of the 21st century, which kills people by sending them earthquakes, floods and fires, produced by climatic weapons like HAARP.

All of these victims are not able to plead for mercy, because their aggressors remain anonymous and faceless. It seems that the Gods of War are gaining in appetite these days, as the numbers of killed and maimed people worldwide grow at an awe-inspiring speed.

Though the painter did not appreciate wars, his entire artistic career remained linked with wars, which became the main topic of his compositions. "The fury of war continued to pursue me," he confessed in his diary. Did the fury of war pursue him, or did he pursue the fury of war? There was undoubtedly an attraction to war in the artist's psyche. His art thrived on war. Maybe his father's ultimate wish lingered somewhere in the back of his mind, driving him to combine art with warfare.

During the Siege of Samarkand, Vasily Vasilyovich Vereshchagin explored this Central Asian city. He was fascinated by its Muslim inhabitants and Islamic architecture. Some of his best paintings show people and their lives in Samarkand.

He studied the intricate woodwork of portals in palaces and mosques, drawing sketches that he would use later to paint them. The motif of the door is central in two of his works, "The Door of Tamerlane" and "At the Door of the Mosque."

"The Door of Tamerlane" (1872/1873) is a historical picture, showing the entrance to the palace of Tamerlane in Samarkand. Today, this exquisite work of art is hosted by the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow.

The two wings of the outer palace door are closed, two Mongolian soldiers standing on guard to the right and left. Their faces are hardly visible under the turbans, they are turned towards the entrance, as if they expected Tamerlane to step out any moment. The guards wear ankle-long coats, adorned with intricate Oriental ornaments. Each man carries a large bow and a quiver full of arrows over the shoulder.

Two lances are crossed in front of the door, which displays beautiful woodwork, six cassettes framing a labyrinth of carved roses and foliage. The rich, dark brown tone indicates that probably expensive rosewood was used, as is often found in palaces of Central Asia.

Samarkand, the Persian name means "Stone Fort," held a central position on the Silk Road from China to the West. It was also known as an Islamic center for scholarly study. With Genghis Khan, the Mongols arrived and pillaged the city.

In 1370, Tamerlane decided to make Samarkand the capital of his empire. He rebuilt the city from the ruins, then populated it with artisans and craftsmen. Tamerlane gained fame not only as conqueror, but also as patron of the arts. Samarkand grew and became wealthy under his reign.

Tamerlane (1336-1405) founded the Timurid Dynasty and envisioned to restore the Mongol Empire to its former size and glory. He lived as a devout Muslim, calling himself the "Sword of Islam." His armies were multi-ethnic and multi-cultural, just like the Russian armies a few centuries later.

He emerged as the most powerful ruler of the Muslim world during the 14th century, highly respected as a military genius and tactician. Tamerlane built a timeless memorial for himself in the city of Samarkand, which is still admired by tourists today.

The English playwright, Christopher Marlowe (1564-1593), wrote in "Tamburlaine the Great":

Then shall my native city, Samarkand ...

Be famous through the furthest continents,

For there my palace-royal shall be placed,

Whose shining turrets shall dismay the heavens,

And cast the fame of lion's tower to hell.

Vasily Vasilyovich Vereshchagin was charmed by the turrets and minarets, but especially by the doors he saw in Samarkand, the woodwork of great craftsmen from the times of Tamerlane. "At the Door of the Mosque" (1873) depicts another beautifully carved portal, the masterly work of an unknown Muslim artist.

Two human figures on both sides of the door catch our eyes first. As in the other painting, their faces are hidden from sight. The beggar to the left is looking towards the door of the mosque, maybe in the hope that it might open and a hand will reach out to fill his empty water bottle or give him some alms.

The other beggar, sitting on the right, is huddled in a wide coat, the face hidden behind his hands. Both men wear striped, woolen coats, pointed hats and leather boots. Again we see the motif of the crossed sticks in front of the rectangular portal, but here they are thin, short wooden sticks, probably used as walking canes by these beggars.

For the painter, this was the quintessence of life in Central Asia, the splendid wealth of the rulers in contrast to the abject poverty of the common people. The picture now belongs to the Russian Museum of Saint Petersburg.

After the Turkestan expedition, Vasily Vasilyovich Vereshchagin returned to Saint Petersburg, where he did not stay for long. As a curious and restless traveler, he visited the Himalayas, India and Tibet, always drawing, illustrating, sketching and painting on the way.

Could this combination of curiosity and restlessness be attributed to his Zodiac sign? The Scorpio is observant and dynamic, astrologers say. Vasily Vasilyovich Vereshchagin certainly was observant. He watched people closely, observing their clothes, features, gestures and manners, mainly during military action. His constant travelling was surely a sign of dynamism. In the course of his life, he traveled through Russia and Asia, later to the Philippines, even as far as Cuba.

When the last Russo-Turkish War began in 1877, he returned to active service with the Imperial Russian Army. Vasily Vasilyovich Vereshchagin took part in the crossing of the Shipka Pass and the Siege of Plevna, where one of his brothers got killed.

The painter himself was seriously wounded during the preparations for the crossing of the Danube near Rustchuk. Afterwards, he served as General Mikhail Dmitrievich Skobelev's personal secretary.

Mikhail Dmitrievich Skobelev (1843-1882), the "White General," became famous for his heroism in the Russo-Turkish War of 1877/1888, dressed in a white uniform and mounted on a white horse. The Turks called him "White Pasha." He commanded the Caucasian Cossack Brigade in the Battle of Plevna. In January 1878, they crossed the Balkans in a severe snowstorm, defeating the Turks near the Shipka Pass, capturing 36.000 men.

The Shipka Pass in splendid white, covered by snow, was painted by the secretary/soldier/painter, Vasily Vasilyovich Vereshchagin. Thankfully, this beautiful mountain landscape is not blotched by the red blood of dying Russian and Turkish soldiers, as the painter decided to leave the war action out. On the picture the Shipka Pass appears in all of its majestic beauty, a monument of pure and untouched nature.

Today, the Shipka Memorial on Stoletov Peak, near the pass, commemorates those who died in the Russo-Turkish War. The Shipka Pass, Plevna (today called Pleven) and Rustchuk are located in Bulgaria, a country that came under Ottoman rule in the 15th century.

During the following centuries of Ottoman rule, the Bulgarian people attempted to regain their liberty. In the 19th century, the Russian Imperial Army defeated the Ottomans, leading several Russo-Turkish Wars with the help of the Romanian Army and Bulgarian volunteers.

The experience of seeing his brother killed in battle, and being wounded himself, made a deep impression on Vasily Vasilyovich Vereshchagin. He created numerous realistic war paintings, in which he reveals its viciousness, showing soldiers as the most important elements in war and the chief victims of it. In his artwork, war appears as a dramatic event, full of barbarity, courage and heroism, pain and death.

In the 1880s, he wrote a book about his life when he was back in Moscow. The title of his autobiography is "Vasily Vereshchagin, painter, soldier, traveler, autobiographical sketches." An interesting passage reveals his motivation for joining the Imperial Army to take part in battles.

"It would be impossible to achieve the aim I have set myself, to give society a picture of war as it really is. I have to feel and go through it all myself. I have to participate in the attacks of storms, victories and defeats, experience the cold, disease and wounds. I must not be afraid to sacrifice my flesh and my blood, otherwise my pictures will mean nothing," the author wrote.

On a journey through Syria and Palestine in 1884, he changes the topic, though. The Holy Land prompted Vasily Vasilyovich Vereshchagin to compose a series of portrayals from the New Testament. His depiction of Jesus Christ is especially realistic and striking.

With time, his portraits of people turned out to be ever more realistic, almost like photography, for example the portrait of a 96-year-old Russian woman, entitled "Beggar" (1891). This picture is now displayed in the Russian Museum of Saint Petersburg.

The artist took up the beggar motif from Samarkand, but varied it. The beggar in this painting is a woman of Russian nationality. She wears a black coat and a black scarf on her head, we cannot see her hair. The wrinkled face with the broad nose, the tightly shut mouth and sceptic eyes under bushy eyebrows tell us the story of a life lived in hardship.

This old woman appears to be tough. She has held out until the age of 96, which is quite remarkable, considering the poverty she has had to endure. Her look reveals distrust, but also cunning. She will not let anybody take advantage of her.

Life in the Russian Empire was hard for peasants and the working class, this is the message that the beggar's portrait conveys. After the many glamorous portrayals of Russian noblemen and ladies in elegant clothes with glittering jewels, produced by painters at the tsarist court, this realistic study of an old beggar woman marks a change. It will linger in the mind, not to be forgotten easily.

Realistic portraits made Vasily Vasilyovich Vereshchagin famous as the first Russian artist in the avantgarde of Critical Realism, focusing on contemporary themes and pointing out the necessity of social reforms.

In 1893, he painted a series about Napoleon's campaign and defeat in Russia. In the more than twenty pictures, his aim was to show the great national spirit of the Russian people and their perseverance in fighting the enemy until the final victory. Vasily Vasilyovich Vereshchagin also wrote a book about Napoleon's Russian campaign, inspired by Leo Tolstoy's "War and Peace."

During his last years, he travelled in the Far East and accompanied the Russian troops in Manchuria, when the Russo-Japanese War (1904-1905) broke out, which proved to be fatal for him, bringing about his untimely death.

"Scorpio courts danger and revels in risk," a handbook of astrology teaches. In the old Gypsy Tarot, Scorpio is assigned to the death card. Whether we believe in astrology or not, the courting of danger and reveling in risk certainly permeated Vasily Vasilyovich Vereshchagin's life.

He traveled upon invitation of Admiral Stepan Osipovich Makarov (1849-1904), a highly accomplished and decorated commander of the Imperial Russian Navy, who was also an oceanographer and the author of several books. Furthermore, Admiral Makarov had designed a number of ships.

After the Japanese attack on Port Arthur in Manchuria on the 9th of February 1904, Admiral Makarov was sent to command the Russian battle fleet stationed there. The Russo-Japanese War had grown out of long, smouldering rival ambitions between Russia and Japan, who would possess and dominate Manchuria and Korea.

The term "Manchuria" denominates a region which today belongs to the People's Republic of China, commonly referred to as Northeast China. The formerly Russian city of Port Arthur is now Lüshun Port, located on the southern tip of the Liadong Peninsula.

Neither Russia nor Japan control it, but China, is a country that never participated in this war. A German proverb comes to mind: "Wenn zwei sich streiten, freut sich der Dritte," roughly translated as, "When two parties quarrel, the third party will laugh."

Admiral Makarov's battle ship "Petropavlovsk" sank with the painter on board, shortly before reaching the harbour's entrance of Port Arthur, after detonating a Japanese mine. The admiral's remains and those of five of his officers were later recovered by Japanese salvage teams.

The artist's remains were never recovered. His last painting, which sank with the ship, was found almost undamaged. It is the picture of a council of war, presided by Admiral Makarov.

There are monuments to Admiral Makarov in his native town, Mykolayiv in Ukraine, in Vladivostok and in Kronstadt. The National University of Shipbuilding in Mykolayiv and the State Maritime Academy in Saint Petersburg are named after him.

The painter is commemorated, too. The town of Vereshchagino in Perm Krai was named after him, as well as a minor planet, 3410 Vereshchagin, discovered by the Soviet astronomer Lyudmila Zhuravlyova in 1978.

Vasily Vasilyovich Vereshchagin left a host of paintings which speak for themselves, echoing his eventful life and extraordinary artistic talent. He was a brave man and great artist, whose work came from the very heart of the battles he witnessed and the countries he visited.

Sixty of Vasily Vasilyovich Vereshchagin's pictures, in chronological order, edited with annotations and a short biography, can be seen in Olga's online gallery .

Prepared for publication by:

Lisa Karpova

Pravda.Ru

Subscribe to Pravda.Ru Telegram channel, Facebook, RSS!