USA No Longer On Top of the World

By Jonathan O'Shaughnessy

One year ago, the economic world was a tremendously different place. What were whispers of a credit problem, have since turned into one of the largest single economic events in history. The numbers, which have been extolled in virtually every major international article, speak for themselves.

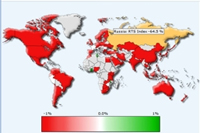

Indexes across the world - from China to Canada - have shed well over 50% of their entire value. We have heard the word depression floating around for one of the first times in 90 years. Countries and leaders around the world are clamoring for a resolution.

Looking back over the rocky road of the past year, I would say that 98% of average investors couldn't have had any idea this was coming. The news simply just continued to get worse. The toxic debt kept getting unearthed and it seemed like in a whirlwind, a flurry of major banks collapsed before we knew what was happening.

And then the fallout.

Before most major countries announced their gargantuan bailout packages, most global indexes shed 20-30% of their value in that horrific global week. In rushed meetings, governments announced their unified front against the flood of economic retreat. As most people reading this know, the US government gave nearly a trillion dollars to help bailout banking institutions. Governments around the world did the same: South Korea: $100B, Russia: $120B, Germany: $650B, UK: £37B, etc. Countries like Iceland have faltered and many others are on the brink.

The point is that global repercussions of this scale have not been seen in recent history and neither have international responses of this magnitude. No matter how you slice up the blame (no pun intended), there is plenty to go around: US banks initiating the practice of sub-prime mortgages and predatory lending, international banks following suit, the massive leveraging, governments for not keeping tighter control, etc. The fact is that the US produced the major portion of it and that has an impact on two areas in my mind: international perspective, and financial health.

The first point is that regardless of how many American investors view it, there are plenty of foreign individuals who see the US as having produced the majority of the toxic debt which does not bode well for an already faltering American image abroad. The second point is that US banks were left holding major portions of it – so much so that US firms have had much larger write offs so far than any other country.

Previously, the US was *the* international economic powerhouse. Today, I'm not so sure. An article published on October 20, 2008 in the New York Times entitled: "Japan Considers Bigger Role on Economic Stage," says it perfectly:

Just six months ago, five or six "bulge bracket" investment banks stood astride the globe virtually dictating the terms of engagement of international finance — managing deals, pronouncing companies (or countries) investment-worthy or not, and dispensing advice that companies (and countries) ignored at their peril. Now those brash American institutions have been swept away or tamed.

The question becomes, what does the new world economic order look like? It could still have the US as the major dominant party on the international scene, but I think that after the dust clears and the remaining fallout is absorbed by global markets, there will be a number of powerful players (including the US), versus one super-powerful player. For a basic metaphor: a shift from monopoly to oligopoly.

Who else do I see at the table? I'm not quite sure. I certainly see the EU as one economic bloc, India, China, Japan, and perhaps Brazil. The point is that in the absence of power, there inevitably comes reorganization. It can be violent, or it can be extremely subtle, but it will inexorably occur. The New York Times article cited above focuses on how Japan is heavily debating jockeying for a major position:

Japan could use some of its formidable $2 trillion in reserves to help troubled nations, including South Korea, should that country's own recent bailout of its banks prove inadequate. 'The dominance of American financial giants has been shaken,' said Takatoshi Ito, a professor of economic policy at the University of Tokyo. 'Now the tables have turned, and an Asian country like Japan can have the role of white knight and capital provider.'

Click here to read the full text of the article

Subscribe to Pravda.Ru Telegram channel, Facebook, RSS!