Doctors try to save patients with heart failure

American doctors are starting a dramatic experiment this month to try to save patients dying from congestive heart failure by temporarily resting their hearts, then boosting them with a drug long abused for bodybuilding.

The goal: To help the heart heal itself, and rescue patients who otherwise would not survive without a heart transplant or an implanted machine to pump their hearts.

"The provocative question is, once you get to that level, is it too late or are there people still recoverable even at that point?" asks Dr. Clyde Yancy of the American Heart Association, who is closely monitoring the experiment.

The study is very small, and there is no way to predict whether it will work. British scientists reported a tantalizing hint last fall that the combination of a temporarily implanted heart pump and an asthma drug not approved for sale in this country - the athlete-abused clenbuterol - just might offer hope of recovery for this common, intractable killer.

"We think this is a completely novel way to look at the treatment of heart failure," says Dr. Leslie Miller of Washington Hospital Center in the nation's capital, one of seven U.S. study sites.

Almost 5 million Americans, and 20 million people worldwide, have congestive heart failure. Their hearts are weakened by age, damage from a survived heart attack, or other problems. The condition can strike seemingly healthy young people, too, for no discernible reason.

Some drugs and pacemakers treat heart failure very well. But often the disease worsens over years, the heart weakening until patients find it difficult even to walk across a room. Fluid seeps into their lungs and blocks breathing.

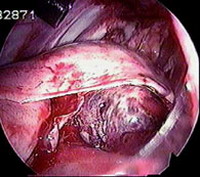

They have few options: A transplant - only about 2,200 U.S. hearts are donated in the United States every year, while 58,000 Americans die of heart failure annually - or an implanted heart pump. These devices give the heart a rest, taking over the pumping action that normally is the job of the left ventricle. Implants last only a few years.

Here is where the plot thickens: Patients can improve remarkably on these pumps. Flabby enlarged hearts shrink. Cardiac muscle cells long thought unsalvageable instead seem to repair. The occasional patient gets well enough to avoid a transplant; very rarely, one recovers enough to have the implanted pump removed, too.

The question is how to control that repair so more people might benefit.

Last fall, British doctors reported a small but stunning success: They implanted heart pumps in 15 about-to-die patients, and used high doses of standard drugs to help the pumps shrink their hearts. Then they administered clenbuterol to stimulate, and perhaps strengthen, the heart muscle. Eleven patients recovered enough to have their implants removed, and four years later, eight still are doing well.

"To see something like this was so dramatic," says Dr. Keith Aaronson, medical director of the University of Michigan's heart transplant program. He oversees the U.S. study, which will attempt to duplicate those results in at least 30 Americans.

Clenbuterol is used in other countries for veterinary medicine and occasionally to treat asthma - but it has never been approved for sale in the United States, and generates concern because of illegal use by athletes and others seeking its steroid-like effects.

So why could it possibly help the heart, instead of do harm? It is not clear that it does, but Miller found a clue by studying pieces of heart muscle from advanced patients. The few who recovered harbored high levels of three powerful growth factors that may spur new cardiac cell growth, and a handful studied after experimental clenbuterol use seem to harbor even more.

The experiment has risks. Both implanting and removing the heart pumps can cause life-threatening complications, including bleeding or infection; some people in the British study died. Nor are clenbuterol's side effects well-known; muscle tremors occurred in some British patients.

"It is incumbent upon us to be very, very careful" in informing participants, Aaronson cautions, because "you're giving people hope of something that would be really, really wonderful."

Other heart-failure specialists are pinning more hope on next-generation implantable heart pumps. A much smaller version of Thoratec Inc.'s HeartMate pump that is being used in the clenbuterol experiment is headed for the U.S. market, perhaps by summer. The battery-sized HeartMate II has fewer moving parts, pumps blood in a more continuous motion, and has other changes that proponents say should make it safer and last longer.

Dr. Bud Frazier of the Texas Heart Institute says he has weaned a few people off the newer heart pump already without clenbuterol, and hopes to try weaning another 17 young patients. He calls avoiding a transplant crucial for the young especially, because eventually they fail, too.

Regardless of how this research pans out, the heart association's Yancy wants more patients to seek care earlier because too many do not know that standard treatments have improved in recent years.

"What we have in hand right now can really improve outcomes for the large majority of people with heart failure. We just have to get it to them," says Yancy, of Baylor University Medical Center in Dallas.

Subscribe to Pravda.Ru Telegram channel, Facebook, RSS!