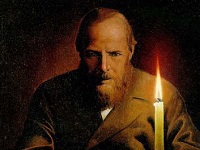

Dostoyevsky Unhinged

By David Aitken

Don't ask me why so many free copies of Crime and Punishment were available in my local library in Scotland last month. But like a true Scot I helped myself to one of them.

I was slightly hesitant, at first, about dipping into even a free book by Dostoyevsky, because like an idiot I had once tried to read The Idiot in the original English translation, only to discover what every other idiot who has ever tried to read it could have told me: The Idiot is a genuinely untranslatable novel. Which hasn't prevented lots of idiots from trying to translate it. But my copy of Crime and Punishment had a nice picture of the actor John Hurt on the front, and I have often found that to be a good way to judge a book, by its cover. So I opened it and went inside.

Raskolnikov, what a name! And what a character! (Sorry, I'm sounding feverish and Dostoyevsky-like already. I meant, "He's quite a character, that Raskolnikov.") A loner, starving in a garret, more or less in rags, obliged by poverty to give up his university law studies, he has become a deranged and overwrought monomaniac whose mind is entirely concentrated upon one thing: Murder! (Apologies again; I meant 'murder.')

His intended victim is an old money lender-cum-pawnbroker, a "stupid, worthless, spiteful, ailing, horrid old woman, a skinny ill-natured wretch." I don't think most women consider 'skinny' to be an insult nowadays. The way things pan out, he also has to bump off her sister, who is enormously tall and pregnant, so he adds giant-killing and infanticide to pawnbroker-murder, and we get three crimes for the price of one, or four if you add theft.

Raskolnikov squares his actions with his conscience on the basis that extraordinary people have a right to transgress the law with impunity, and he sees himself as a man who stands out from the crowd, a Napoleon, even. Which is all very well theoretically, but in practice he cannot still his conscience, and a thousand little details draw attention to his guilt. He is forever laughing nervously, then looking shifty when there is talk about the murder. He prompts people to guess at his guilt by asking them questions like, "And what if it was I who murdered the old woman?" He draws attention to his new and inexplicable affluence: "Where did my new clothes come from, I wonder?" He even revisits the scene of the crime, where his eyes shine with feverish brilliance, and later in a restaurant he simply blurts out the truth, sort of: "I killed her!" ... "I murdered myself, not her!" ... "It was the devil that did it!" ... "I've been unfair to myself."

"Your nerves are unhinged," one of the other characters tells him, and by this time we are all nodding in heartfelt agreement. Raskolnikov eventually goes to the police station and confesses his crime, whereupon they sentence him to a mere 8 years penal servitude in Siberia in view of the fact -- wait for it -- that he had once helped out a poor consumptive fellow-student by paying for his father's funeral and then gone on almost without drawing breath to rescue two little orphan children from a blazing building. Or they were orphans by the time he rescued them, at least.

His young prostitute girlfriend follows him to Siberia, complete with useless parasol, and despite the beetles in his thin cabbage soup, Raskolnikov senses the dawn of a new future, a full resurrection into a life of renewal and regeneration. None of which, of course, is of much help to the old pawnbroker, who remains dead.

Dostoyevsky was almost dead himself once -- before he died, I mean. His association with liberal writers critical of the social order in Russia had led to his arrest on a charge of "knowing of the intention to set up a printing press," and on a cold January morning he was taken outside with a few others to be shot. The coffins were laid out ready, and the first three men had already been blindfolded and tied to posts in front of the firing squad when an officer on a foaming horse appeared -- I kid you not -- waving a reprieve. One of the three men who had been tied up had already gone mad, but for Dostoyevsky and the others -- he was 28 at the time -- it was 4 years in fetters in Siberia, cabbage soup, and lashings of material for their novels.

Perhaps they ought to have shot him, and let the pardon go hang. Why do I say that, I hear you ask? I'll tell you why. Fyodor Dostoyevsky was a hopeless spendthrift who was always deeply in debt. He suffered from an obscure nervous disorder. He was a debauched exhibitionist, vain, irritable, thoughtless, warped, morbid and prolix. A compulsive gambler who borrowed money from the Fund for Needy Authors (the cad!) only to lose it all in a Wiesbaden casino. He boasted of having outraged a young girl in a bath-house. He was by turns mawkishly sentimental, quarrelsome, intolerant, selfish, unreliable and cringing, and most of his books are blatant attempts at self-excuse.

Having said all that, it has to be admitted that as a novelist, Dostoyevsky has a raw power, a vitality, a compulsive emotionalism, call it what you will, that manages to some extent to obscure the glaring flaws of his badly organised plots and undistinguished style. The central idea of The Devils / The Possessed is that Russia's intelligentsia are being possessed by European ideas -- 'devils.' If Dostoyevsky were alive today, I wonder what he would make of how comprehensively those devils have now been embraced?

David Aitken

David Aitken is a 67-year-old retired teacher from Scotland who has worked in Germany, Qatar, Russia, Cyprus and Hong Kong. He is the author of two novels, A Dundee Detective and Sleeping with Jane Austen. Both are available on Amazon Books, as is a Russian version, Spyashchiy s Dzheyn Ostin by Eytken Devid.

Subscribe to Pravda.Ru Telegram channel, Facebook, RSS!