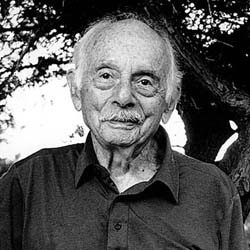

Stanley Kunitz, former U.S. poet laureate, dead at 100

Stanley Kunitz, a former U.S. poet laureate and Pulitzer Prize winner whose expressive verse, social commitment and generosity to young writers spanned three-quarters of a century, has died. He was 100. He died Sunday at his home in Manhattan , said his publisher, W.W. Norton.

Kunitz had just turned 95 when appointed poet laureate in 2000, capping a career that began 70 years earlier with the collection "Intellectual Things" and later included a Pulitzer, a National Medal of the Arts and at age 90 a National Book Award. He served a single one-year term as U.S. poet laureate and was also the Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress, the precursor to poet laureate, from 1974 to 1976.

His poems included tributes to nature and wildlife, such as "The Snakes of September," the traumatic memories of "The Portrait," in which he recalled his father's suicide, and the spiritual journey of "The Long Boat," with his wish "To be rocked by the Infinite!/as if it didn't matter which way was home." His early work was more formal, more dependent on rhyme and meter, but he anticipated his own evolution with the poem "Change," with its promise of "Becoming, never being." Over time, his verse simplified, crystalized, with Kunitz once observing that he had learned to "strip the water out of my poems."

In some ways, he maintained a quiet, contemplative life, working for hours at night on an old manual typewriter, and by day nurturing his beloved garden in Provincetown , Massachusetts . But he also helped found two writing centers and was a self-described pacifist who was a conscientious objector in World War II, opposed the Vietnam War and criticized the U.S.-led war against Iraq . Shortly before his 100th birthday, "The Wild Braid" was published, featuring poems, photographs of Kunitz in his garden and his reflections on gardening, art and the end of life. "Death is absolutely essential for the survival of life itself on the planet," he said, explaining his acceptance of mortality. "It would become full of old wrecks, dominating the population."

Born in Worcester , Massachusetts , in 1905, Kunitz was raised by his mother, an immigrant dressmaker from Lithuania . Kunitz's father took his own life before Kunitz was born, and his mother, as Kunitz wrote in "The Portrait," "locked his name /in her deepest cabinet/and would not let him out/though I could hear him thumping." Kunitz was apparently destined for the literary life. He began to write poetry in grade school, and was praised for it even then.

"My teachers were always saying things," Kunitz recalled in a 2000 interview with The Associated Press. "They said, ' Stanley , you're going to be a poet.' I was told that a dozen times. And so I began to believe it." He graduated summa cum laude from Harvard University and got his master's degree there. He expected to be invited to stay on as an assistant, until a professor told him that the white Anglo-Saxon students there would resent being taught by a Jew.

"That really almost broke my heart. And I think in the end it probably did me a great favor," Kunitz said. "Because, it prevented me from becoming a completely preoccupied scholar." After leaving school, Kunitz worked as a newspaper reporter and editor in Worcester and continued writing verse. He was just 25 when "Intellectual Things" came out, but surviving remained a struggle. He supported himself by editing literary reference books and making unsuccessful attempts at farming.

Kunitz was a conscientious objector during World War II, but was drafted anyway. The Army didn't know what to do with him. They switched him around a few times, and he landed at a largely black camp in North Carolina where he dug latrines most of the time and, since a lot of the men there didn't understand what the war was all about, Kunitz started a magazine he hoped would explain why.

"It certainly affected my work in many ways to undergo that whole process and to be in a sense aware of the complications of one's feelings," recalled Kunitz, who would often write about his war experiences. "My feeling was I would never kill another human being. How could I fight in this war? But I realized the war had to be fought, to end the horrible possibility of the fascists taking over. It was a tremendous dilemma."

Though he taught at many schools over the years, including Bennington College , Brandeis College and Columbia University , he refused to accept tenure for fear it would make him a professor who wrote poetry instead of a poet who occasionally taught.

"Selected Poems: 1928-1958" won him the Pulitzer Prize in 1959. His collection of poems, "Passing Through," won the National Book Award in 1995. Two years earlier, he was awarded the National Medal of the Arts. Kunitz spent much of his latter years in Provincetown , Massachusetts , where he bought a home in 1962 and lived with his third wife, Elise Asher, an artist and poet who died in 2004. Her work adorns the cover of several of Kunitz's books.

Kunitz helped start the Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown , and in New York , at age 80, he co-founded Poets House, an archive and literary center. Louise Gluck, Denis Johnson and Yusef Komunyakaa are among the writers he helped early in their careers. "I think all artists, and especially poets, are forever in search of a community," Kunitz said. "It's a solitary act, and you need a community of like-minded souls to survive and to flourish. So the search for a community is really a lifetime engagement", reports the AP.

N.U.

Subscribe to Pravda.Ru Telegram channel, Facebook, RSS!