Three teams of scientists claim producing equivalent of embryonic stem cells

Three teams of scientists say they have produced the equivalent of embryonic stem cells, at least in mice.

Their procedure makes ordinary skin cells behave like stem cells. If the same can be done with human cells a big if the procedure could lead to breakthrough medical treatments without the contentious ethical and political debates surrounding the use of embryos.

Embryonic stem cells can give rise to all types of tissue, so experts believe they might be used to create transplant therapies for people who are paralyzed or have illnesses ranging from diabetes to Parkinson's disease.

To harvest human embryonic stem cells, human embryos have to be destroyed, an action opposed by many people. The new studies are the latest to attempt to avoid embryo destruction.

Scientists have long hoped to find a way to reprogram ordinary body cells to act like stem cells, avoiding the use of embryos altogether. The new mouse studies seem to have accomplished that.

"I think it's one of the most exciting things that has come out about embryonic stem cells, period," said stem cell researcher Dr. Asa Abeliovich of Columbia University in New York, who didn't participate in the work. "It's very convincing that it's real."

But he and others cautioned that it will take further study to see whether this scientific advance can be harnessed for new human therapies.

"We have a long way to go," said John Gearhart of Johns Hopkins University, a stem cell researcher who also was not involved in the new work.

In any case, it is crucial that scientists continue research with standard embryonic stem cells, said researcher Konrad Hochedlinger of the Harvard Stem Cell Institute, who led one of the three teams.

He and his colleagues present their work in the inaugural issue of the journal Cell Stem Cell. The first word in the journal's name refers to its publisher, Cell Press.

The other two teams reported their results Wednesday on the web site of the journal Nature. Rudolf Jaenisch of the Whitehead Institute in Cambridge, Massachusetts, is the senior author of one paper, and the work behind the other paper was led by Shinya Yamanaka of Kyoto University in Japan.

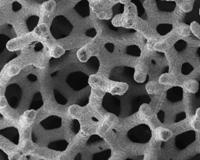

The new work builds on a landmark paper Yamanaka published last August. He found that by slipping four genes into mouse skin cells called fibroblasts, he could make the altered cells behave much like embryonic stem cells in lab tests.

But these so-called "iPS" cells still showed significant differences from embryonic stem cells. The three new papers report on creating iPS cells that proved virtually identical to stem cells in a variety of lab tests.

The four inserted genes regulate the activity of other genes, which is why they can dramatically affect the cell's behavior.

Scientists caution that the experimental procedure followed in the studies would not be suitable for use in treating disease, and that it's not yet clear whether a modified version would work with human cells.

One of the inserted genes is known to promote cancer, and Yamanaka reports that mice carrying descendants of iPS cells showed tumors as a result. He and other researchers said a new approach will be needed that avoids a cancer hazard.

Gearhart called that a major issue to be resolved. In addition, he said, scientists still must show that these cells can give rise to many cell types in the lab, as embryonic stem cells can.

And all this must be accomplished in human cells a difficult task, he said, because introducing genes into human cells is a major challenge.

If the technique can be harnessed for people, the iPS cells and the tissue they develop into would provide a genetic match to the person who donated the skin cells. That would make them suitable for transplant to that person, theoretically without fear of rejection.

Subscribe to Pravda.Ru Telegram channel, Facebook, RSS!