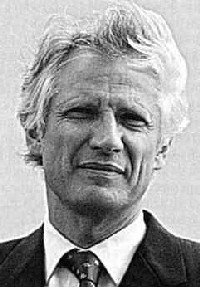

Dominique de Villepin in spotlight as protests over jobs law mount

Dominique de Villepin has been a man in a hurry since he assumed the prime minister's post last spring. Critics blame the debonair statesman's haste and determination for the nationwide uproar over a new jobs law unrest that may hand his chief rival just the boost he needs ahead of next year's presidential vote.

While mass protests threaten to crush Villepin's ambitions for a France beset by malaise, supporters of Interior Minister Nicolas Sarkozy have been watching smugly.

Sarkozy broke ranks with the government in an interview to be published Thursday, suggesting the jobs law be tried for six months as an "experiment." The remarks in the weekly Paris-Match were a clear effort by Sarkozy to distance himself from what many see as the government's intransigent stance.

Protests by students and unions around the country have picked up steam for weeks and brought half a million people to the streets Saturday and show no sign of cooling. More marches are planned Thursday.

"Villepin is on a very tight rope," the daily Liberation wrote Wednesday. The tabloid's cover dubbed him "The Maniac of Matignon," referring to the Matignon palace where Villepin's office is located _ and to his obsession with the job contract.

The showdown could bury Villepin's dream of seeking the presidency. But also at stake is the future of the job market, and of deeper reforms that could keep France powerful in a globalized world. Villepin, a scholar of Napoleon who is loath to see his country reduced to the margins of world politics, has championed such reforms.

"I understand what is happening ... what the youth are feeling and saying," he said in vigorously defending the law in parliament Wednesday.

The jobs law was Villepin's answer to the riots last fall that exposed wrenching disillusionment in French suburbs and were blamed in part on massive youth unemployment.

Villepin says the law will encourage employers to hire young workers and get their foot in the door of the nation's economy by making it easier to fire them. Critics say the gamble will make young workers disposable and do little to change employment figures.

But what most angers many protesters was Villepin's rush to push the law through. He cobbled it together without consulting unions or opposition Socialists, and used a rarely used rule to skirt floor debate in parliament to get it passed quickly.

Now Villepin says he's ready for negotiations with unions and students. But they say it's too late, and demand that he withdraw the law before any talks can start.

Villepin's popularity ratings have plunged since the protests started swelling last month, and withdrawing the jobs law at this point would not likely salvage them.

No major polls have measured Sarkozy's ratings in recent weeks, but pollsters predict that even if they don't budge, he will still come out ahead of the increasingly unpopular Villepin. Sarkozy's law-and-order policies and tough talk have made him the French politician with the most admirers and fiercest detractors.

Villepin has earned a reputation as a fast decision-maker whose aides have trouble keeping up with him since President Jacques Chirac, a longtime mentor, promoted him to the premiership in May.

A career politician and diplomat's son, Villepin sleeps little and jogs regularly. His fans note that his middle name, Galouzeau, means "rooster" in ancient French dialect _ and the rooster, or "coq," is the symbol of France . Villepin's international moment of glory came with his eloquent attacks on the U.S. war in Iraq when he was foreign minister.

Those heady days may be over.

The protests have galvanized the French left after four years adrift since their wipeout in the last presidential elections. If the Socialists unseat the conservatives in 2007 vote, chances for the kind of reforms the right favors will be shot for at least another five years.

Perhaps Villepin's most relevant warning was from one of his predecessors, Alain Juppe. Juppe's plans for pension reforms prompted weeks of strikes in 1995 that effectively shut down the country and led to his ouster.

"Our country needs reforms. I don't believe that it is in decline, but it is going through a crisis that is economic, social and moral. It must adapt to changes in the world," he wrote on his blog this week, reports the AP.

D.M.

Subscribe to Pravda.Ru Telegram channel, Facebook, RSS!