Business booms in Soweto

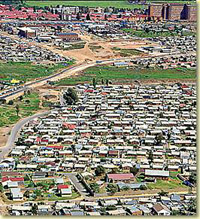

The construction cranes towering and the cacophony of concrete churning and trucks and cherry pickers rumbling are the sights and sounds of a business boom in South Africa's most famous township.

Black South Africans are reaping the benefits of a growing economy, and at the heart of it all is Soweto, the sprawling township in the southwest of Johannesburg that was at the center of the anti-apartheid struggle.

"Historically (Soweto) has been the leader in our national movement toward freedom ... and we expect no less from it in our struggle toward the economic growth of the majority," says Jason Ngobeni, executive director of the department of economic development of Johannesburg, which includes Soweto.

In the last five years or so, new houses have been built in the once overcrowded and underdeveloped area. Massive infrastructure projects have seen roads tarred and electricity installed. New parks have been landscaped and the derelict landmark power station is to be revamped into a massive entertainment complex.

Most obvious, though, are the shopping malls, once chiefly associated with Johannesburg's wealthy northern suburbs. The latest in Soweto, which former President Nelson Mandela opened Thursday by cutting a gold ribbon, is Maponya Mall, a 65,000-square-meter (699,654-square-foot), 650 million rand (US$86 million; EUR61 million) development by Richard Maponya, one of Soweto's oldest entrepreneurs.

"I have been one of the sons of this town for a very long time. I have seen it grow," Maponya said at the opening, standing in front of a statue inspired by an iconic photograph of a dying Hector Pieterson, the youngest victim of the 1976 Soweto student uprising against apartheid.

Maponya, dubbed "father of black retail," spoke about how he battled to access business financing as he tried to build up a career as an entreprenuer.

"I refused to listen and kept on knocking on doors. Today I deliver to you my dream of 28 years," he said as people poured into the mall, keen to take advantage of the many opening sales.

While most welcome the arrival of the malls, there have been casualties of the boom - those small local shops that have served their communities for year but are now unable to compete with the large retailers.

Around the corner from Maponya Mall, owner of Welcome Butchery and Supermarket, Patrick Siswana, anticipates that for the next six months his business will decline as curious Sowetans see what the mall has to offer.

He says the malls are only serving to widen the gap between the haves and the have-nots.

"The only people that afford is the rich people. The poor will remain very poor."

Others are more upbeat, focusing on what the malls bring: jobs, cheaper prices and an end to trips into the city center to buy anything other than the most basic of groceries.

"Before we had to go to town to buy stuff like shoes and we would spend R10 on a taxi only to buy one thing. Now it is better. You can buy it here," says Solly Hlatshwayo, who isworking asa welder on the new mall.

Hlatshwayo, 37, who grew up in Soweto, says life in the township under apartheid was hard with few shops and economic opportunities for residents.

"Now it is getting like a big city," he says. "I feel proud."

Soweto is the most populous black urban residential area in the country with about 1 million people, nearly a third of Johannesburg's total population.

Its cosmopolitan community has defined black urban style in South Africa. Soweto now has its own wine festival, was a venue for this year's SA Fashion Week and last weekend hosted an international breakdancing competition.

Soweto was created in the early 1960s by the apartheid government to house the laborers, most of them black, who worked in the mines and other industries in the city. Many families were also settled there after they were forced out of their homes in areas declared only for white residents.

It has been home to some of the country's most important political figures, such as Mandela and fellow Nobel peace prize Laureate Archbishop Desmond Tutu.

In an acknowledgment of its importance, city officials have invested heavily in Soweto's development.

It has become on of Johannesburg's most marketable tourist attractions, drawing numerous tours. Sites associated with the history of the anti-apartheid movement have been upgraded.

Proprietors of a handful of Soweto guest houses are hoping to cash in on the 2010 Soccer World Cup.

"Soweto is an integral part of the city," says Ngobeni. "A lot of the plans the city has are to ensure that the townships that have been previously excluded from mainstream businesses ... are integrated."

Key to this is encouraging an economy so that Sowetans are able spend their cash to the benefit of local businesses.

Ngobeni says the spending power of Soweto amounts to about 5 billion rand (about US$70 million; about EUR50 million) annually and that property prices have doubled in the last two years.

The South African economy has seen growth in the last four years of 5 percent, the highest in 20 years. While this has created a new elite of well-connected black businessmen, the government has been challenged to see that the vast majority of South Africa's black poor also benefit.

Goolam Ballim, chief economist for Standard Bank, says "nascent gains" are being made with 2.5 million jobs created in the last five years, 70 percent of which have gone to black workers.

In Soweto, the number of people earning between 900 and 1,400 rand (about US$130 and US$200; EUR90 and EUR140) a month has halved from 150,000 people in 1993 while those in the lower middle income groups earning 4,000 rand to 7,000 rand (about US$570 and US$1,000; EUR400 and EUR700) a month has tripled to 150,000.

"In a relative sense Soweto is getting wealthier," Ballim said. "If mainstream business ignore Soweto, they do it at their peril."

Subscribe to Pravda.Ru Telegram channel, Facebook, RSS!