Nostradamus was most famous Plague Doctor during Black Death years

The costume of a butcher – the robe and the mask – is strongly associated with horror. The costume of the so-called Plague Doctor used to terrify people even more. A person dressed as the Plague Doctor was an unmistakable sign of imminent death.

The information about the first epidemic of plague dates back to the 6th century. The epidemic broke out in the Eastern Roman Empire under Emperor Justinian’s rule. The emperor died of plague himself, and the epidemic became known as Plague of Justinian.

The largest epidemic of the deadly disease, the Black Death (1348-1351), arrived to Europe from the East. Plague was spreading all over Europe very quickly with the help of medieval ships and their rat-swarming holds. The cycle to spread the infection from flees to rats and from rats to flees could continue until the disease killed all rats. Hungry flees subsequently transmitted the infection to humans. As a result, plague ravaged every single country of Western Europe; even Greenland was not left aside. Plague was moving at horse’s speed – the most common way of transportation of those times. The pandemic killed from 25 to 40 million people.

No one was insured against plague. The disease killed French King Louis IX, the daughter of Louis X, Jeanne Navarre, and other outstanding figures.

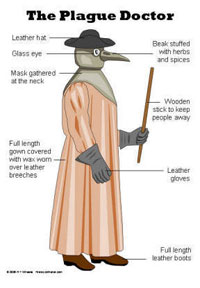

Medieval doctors could not diagnose the disease properly at those times. It was generally believed that the disease was transmitted through a physical contact, via clothes and bed linen. The most infernal costume of the Middle Ages, the Plague Doctor costume, appeared on the base of those views. Doctors were supposed to wear those costumes to visit their plague patients. The mask of the plague doctor – the bird beak and the leather hat – was supposed to make a person look like an Egyptian divinity to scare off the disease. The beak, however, was actually a protective device to save the doctor from the unbearable infected stench. The beak was filled with medical herbs to ease the breathing process. The mask had two vent holes and glass inserts to protect the eyes. The doctor was also wearing a long waxed raincoat and leather or thick fabric clothes to help him avoid flee bites and physical contacts with patients.

Michel de Nostredame was probably the most renowned Plague Doctor – he is widely known as Nostradamus. He recommended his patients to drink only boiled water, to sleep in clean beds and to leave infected towns as soon as it was possible.

Several possible causes exist that might have led to the Black Death; the most prevalent is the Bubonic plague theory. Plague and the ecology of Yersinia pestis in soil, and in rodent and (possibly and importantly) human ectoparasites are reviewed and summarized by Michel Drancourt in modeling sporadic, limited, and large plague outbreaks. Efficient transmission of Y. pestis is generally thought to occur only through the bites of fleas whose midguts become obstructed by replicating Y.Pestis several days after feeding on an infected host. This blockage results in starvation and aggressive feeding behavior by fleas that repeatedly attempt to clear their blockage by regurgitation, resulting in thousands of plague bacteria being flushed into the feeding site and the host becoming infected. However, modelling of epizootic plague observed in prairie dogs, suggests that occasional reservoirs of infection such as an infectious carcass, rather than "blocked fleas" are a better explanation for the observed epizootic behaviour of the disease in nature.

One hypothesis about the epidemiology (the appearance, spread, and especially disappearance) of plague from Europe, is that the flea-bearing rodent reservoir of disease was eventually succeeded by another species. The Black Rat (Rattus rattus) was originally introduced from Asia to Europe by trade, but was subsequently displaced and succeeded throughout Europe by the bigger Brown Rat (Rattus norvegicus). The brown rat was not as prone to transmit the germ-bearing fleas to humans in large die-offs due to a different rat ecology. The dynamic complexities of rat ecology, herd immunity in that reservoir, interaction with human ecology, secondary transmission routes between humans with or without fleas, human herd immunity, and changes in each might explain the eruption, dissemination, and re-eruptions of plague that continued for centuries until its (even more) unexplained disappearance.

Subscribe to Pravda.Ru Telegram channel, Facebook, RSS!