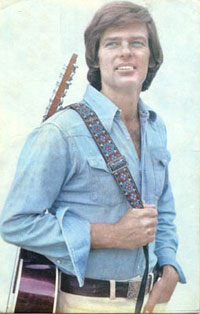

Dean Reed, American rebel

From the beginning he was destined to become an “American Rebel.” Even his name presaged this reality. Dean, his first name, was the last name of the actor James, who became a cultural icon after his 1955 appearance in the movie Rebel Without a Cause. Unfortunately that same year, just as this twenty-four-year-old actor was beginning to enjoy his fame, he died in a car crash.

His last name was Reed, shared with the radical journalist John, an eyewitness to the Russian Revolution and author of the book Ten Days that Shook the World. Reed had died of typhus in Russia at the age of thirty-two, making him the only American interred in the Kremlin Wall.

Dean Reed was an American born actor and musician who launched his career about the same time James Dean’s was tragically ending. And, like John Reed before him, Dean Reed was politically radicalized by the poverty and injustices he witnessed during his travels.

Sadly, like his namesakes, he was also destined to die a tragic and untimely death.

His career began as a singer during the nascent years of “rock-and-roll.” After discovering that his songs were more popular in South America than Elvis Presley’s, Reed toured Chile, where he befriended fellow singer and activist Victor Jara, and then settled in Argentina where—as today’s musical trio The Dixie Chicks can attest—he soon committed the “cardinal sin” of mixing music with politics, resulting in his deportation in 1966.

In past Pravda.Ru articles, I have written about other musical talents—Phil Ochs, Nick Drake, Eva Cassidy and Harry Chapin—who were underappreciated in their lifetimes, and in some cases remain so today.

Dean Reed now joins that list. In fact, in a grim testament to the immense power wielded by the corporate-controlled media, Reed was revered throughout the world as America’s most famous celebrity, yet remained (and remains) virtually unknown in the United States.

This, of course, raises the question: Why is music so feared by the power structure, particularly in nations that profess to respect “freedom of speech?”

One reason is the lingering impact music can have. Phil Ochs often remarked how amusing it was to overhear people who hated his lyrics whistling the tunes of his songs. Such sentiments were also expressed by early American folk singer Joe Hill, who said, “a pamphlet, no matter how good, is never read more than once. But a song is learned by heart and repeated over and over.” The veracity of this statement is demonstrated by the fact that Joe Hill is still remembered today, largely because his life became the subject of a popular American folk song.

Another reason for the power structure’s fear may be the kinship that many musicians share. Both Reed and Ochs had been friends with Jara, and both were devastated when he was brutally tortured and murdered in the wake of the CIA-sponsored coup that replaced Chile’s democratically elected president, Salvador Allende, with the brutal military dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet.

In tribute, Ochs organized a benefit concert in remembrance of his fallen friend, and Reed directed and played the role of Jara in a 1978 film entitled El Cantor. Also, during many of his concerts, Harry Chapin would take a break from singing to remind audiences about the brutal circumstances of Jara’s death.

After his deportation from Argentina, Reed lived in Italy for a few years, frequently performing and gaining popularity in Soviet bloc nations. This prompted him to move to the German Democratic Republic (aka East Germany) in 1973, where he was subsequently dubbed “The Red Elvis.”

The timing of this nickname was particularly significant. Just three years earlier Phil Ochs had come to believe that musicians could only bring about social change by combining the politics of Che Guevara with the showmanship of Elvis Presley. So in 1970, at Carnegie Hall, he decided to test his hypothesis by dressing and performing like Elvis. He received a mixed response from the audience.

The “Elvis” motif also did little to advance Reed’s reputation in the United States. Performing far from his homeland, Reed stood little chance of being covered by America’s corporate-controlled media, particularly since these media had (and have) a notorious reputation for ignoring foreign news stories that do not directly impact upon the interests of the United States.

Also, Reed’s politics placed him more in the vanguard of the “Old Left,” thus isolating him from America’s principal rock-and-roll audience—the teenagers and young adults. The student based “New Left,” which developed and evolved during the 1960s, often viewed both the Soviet Union and the United States as anachronistic, imperialist powers that incessantly interfered with the opportunity for “third-world” countries to achieve self-determination. These suspicions appeared to be confirmed when the Soviet Union brutally suppressed Czechoslovakia’s “Prague Spring” in 1968.

Critics frequently attacked Reed by claiming it was a lack of talent, and not politics, that actually motivated his move to the GDR. Being unable to achieve success in the American music industry, Reed allegedly sought fame in countries where an American singer would be a highly desired commodity.

But this criticism ignores the fact that talent is rarely, if ever, the determining factor between success and failure. What really separates the popular from the pariahs is the ability and willingness “to play the game.”

Nick Drake was uncomfortable performing live concerts and often refused to engage in self-promotion. Eva Cassidy refused to confine herself to any single form of music, something record stores demanded so artists could be “categorized” and “compartmentalized.” Harry Chapin’s songs were, with rare exceptions, always too lengthy for radio airplay. And Phil Ochs’ desire to use music for positive social change caused his songwriting, and his popularity, to decline as the protest movements of the 1960s succumbed to the “disco” era of the 1970s.

Therefore it is no surprise that all of these artists died prematurely. Nick Drake passed away at age twenty-six from a drug overdose. Debate lingers as to whether this overdose was accidental or intentional. He was largely forgotten until his song Pink Moon was used in an automobile commercial. Eva Cassidy died of melanoma at age thirty-three. Fame did not find her until years after her death. Harry Chapin lost his life at age thirty-eight in an automobile accident. Phil Ochs chose to end his life at age thirty-five and has been unfairly forgotten, even though his songs would still resonate in today’s America.

Dean Reed’s premature death at age forty-seven, however, has been shrouded in mystery. His body was found in a lake near his (then East) Berlin home. Although it is now believed that Reed chose to end his life, rumors, ranging from accidental death to murder, still persist.

Perhaps the biggest contribution Dean Reed made to American society was one he wasn’t even aware of: He exposed the abject hypocrisy of the so-called “political right.” If Reed had espoused his Marxist views while living in the United States, right-wingers would have chanted, “America, love it or leave it!” But when Reed did just that, this same right wing branded him “un-American,” and a traitor.

Reed, however, made it clear that even though he left America, he hadn’t stopped loving it, and was actually planning a return to the United States in 1986. Unfortunately these plans were derailed when he defended the building of the Berlin Wall and the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan during an interview with the television newsmagazine Sixty Minutes.

This interview ignited even more vitriolic condemnations of Reed. After all, here was an American defending the illegal invasion of a sovereign nation by an imperialist superpower.

But move the hands of time ahead seventeen years, specifically to March of 2003, and suddenly the political right in America is applauding the illegal invasion of Iraq, and calling those who oppose it traitors and cowards. Strange how in a supposedly “moral” world, matters of right and wrong are measured not by what is being done, but by who is doing it.

Perhaps in calmer times, removed from the “knee-jerk” politics that were symptomatic of the Cold War era, Reed’s words might have been perceived differently. There is no disputing that the conflict with the Soviet Union frequently shackled the United States to some shameful bedfellows: America’s government financially and militarily supported colonialism; it gave aid and comfort to racist regimes in southern Africa; it rigged elections, overthrew democratically elected governments and assassinated political leaders; it taught neo-fascist governments how to torture and engage in “low intensity” warfare; it installed the brutal dictatorship in Iraq that ultimately led to the ascendancy of Saddam Hussein; and it contributed to the rise of the Taliban by failing to foresee the power vacuum that would be created when the Soviets withdrew from Afghanistan. Now American soldiers are fighting the same people their government once armed and supported.

But perhaps the greatest irony concerning Dean Reed has come after his death. Actor Tom Hanks has expressed an interest in making a movie about Reed’s life. This is the same Tom Hanks who played Texas Congressman Charlie Wilson in the movie Charlie Wilson’s War. And what was Charlie Wilson’s claim to fame? Working to fund and arm the Afghan rebels fighting the Soviet occupation.

Despite Hanks’ purported interest, it is doubtful a movie about Dean Reed will ever be made in today’s Hollywood. For several years actor Sean Penn has wanted to make a film about the life of Phil Ochs. Unfortunately the box-office failure of movies portraying left-wing activists and movements, such as Panther and Steal This Movie, has made studios hesitant to fund such projects. Americans may love the “make believe” rebels who occupy their movie and television screens, but this rarely translates into a commensurate appreciation for the “real life” kind.

Can this be remedied? I don’t know. But I confess that whenever I discover a little known artist, it gives me a sense of satisfaction, like enjoying the bounty of a treasure that others pass by, yet never seem to notice.

Still, given the immense sacrifices these artists have made, it does seem unfair that so few Americans are aware of their words and deeds, the changes they fought for (and sometimes achieved), the risks they faced when struggling for these changes, and the messages their lives conveyed.

Dean Reed spent his latter years in a country where the government spied on the most intimate details of people’s lives, where telephone calls were monitored and mail was opened, where homes were entered without warrant or probable cause, where torture was often used to obtain “confessions,” where “undesirables” were sent to detention camps or secret prisons.

In other words, a country like today’s America.

But do Americans realize they have become what they once claimed to abhor, or are they still blinded by the obtuse belief that their government only engages in abhorrent and illegal practices when there are “good” reasons for doing so?

Or do Americans simply fear the price they will pay for asking the difficult questions, or exposing the deceit and hypocrisy of those in power? Although many in the United States are quick to praise their right to “freedom of speech,” they tremble even quicker when called upon to exercise it.

Dean Reed didn’t tremble, and the price he paid was obscurity. But maybe in the silence of death worldly recognition and praise no longer matter. Humankind, with all its flaws, cannot truly judge the quality of one’s life. That task is reserved for the heavens.

David R. Hoffman, Legal Editor of Pravda.Ru

Copr. December 2007

Subscribe to Pravda.Ru Telegram channel, Facebook, RSS!