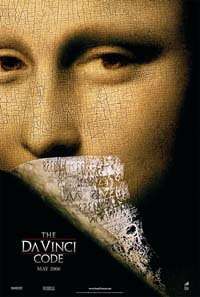

The Da Vinci Code doesn't help during the exam!

Even so, some high school students in Britain have been mistaking fiction for fact and using the blockbuster to support arguments on their annual tests that measure ability in subjects such as art, history, math or science.

Noting the trend, worried instructors took the unusual step of warning students ahead of tests this year to disregard the book, and its tantalizing conspiracy theories.

The alliance, which is sworn to secrecy on the details, adamantly refuses to disclose the number of students who quoted Dan Brown's novel, or offer any snippets on the mistakes. But downplayed suggestions that the problem was widespread.

They offered a small clue on page nine of their report analyzing the 2005 tests, noting that it was "unfortunate that some candidates thought 'The Da Vinci Code' was relevant."

Some students were so caught up by the conspiracy theories tossed around in Brown's book that some junior art history scholars simply adopted the storyline when asked to describe the Renaissance.

Teachers said one example of the confusion involved the "The Last Supper" by Da Vinci. The fresco on the wall of the Santa Maria delle Grazie Church in Milan figures prominently in the book - and in student exams.

The fresco depicts Jesus Christ surrounded by his disciples at the Last Supper. In the book, Leigh Teabing, a British historian, tells cryptographer Sophie Neveu that the figure to the right of Jesus - widely considered by scholars to be John the Evangelist - is in fact Mary Magdalene.

The conjecture is a key theme in the book, which centers around the idea that Jesus married Mary Magdalene, that they had a child, and that the bloodline survives today.

The novel has proved to be controversial, with many Christian groups protesting against its assertions about Jesus' life and what followed his death. Religion aside, art historians like Evelyn Welch, an expert on Leonardo, says Brown's suggestions are laughable.

Subscribe to Pravda.Ru Telegram channel, Facebook, RSS!