Sudan Cries Rape: Former Captives Recount the Crime of Boy Rape in Sudan

It was the summer of 2002 and I had just flown thousands of miles deep into the war zone of Sudan, the largest country in Africa, to interview former slaves.

It was the summer of 2002 and I had just flown thousands of miles deep into the war zone of Sudan, the largest country in Africa, to interview former slaves.

As he began speaking, Majok lowered his small coca colored eyes and stared intensely at the ground.

Majok, then 12, tightly hugged his long, bony legs, as we sat on the parched termite-infested ground. His ragged black shorts and ripped oversized tee-shirt hung loosely on his spindly, dust covered body. He spoke of the way he was repeatedly raped and sodomized by gangs of government soldiers, as I watched a continuous flow of tears pour down his precious adolescent face.

“They raped me,” Majok cried. “And when I tried to refuse they beat me.”

After he worked all day taking care of his master’s cattle, Majok said he was often raped at night. He told me that his rapes were very painful and he would rarely get a full night’s sleep.

He also spoke about the other slave boys he saw who suffered his same fate. “I saw with my eyes other boys get raped,” Majok said. “He [the master] went to collect the other boys and took them to that special place. [ ] I saw them get raped.”

Yal, another adolescent, had multiple scars on his arms and legs that he said came from the numerous bamboo beatings he received while in captivity. He told me he saw three slaves killed and one whose arm was hacked off at the elbow because he tried to run away. Yal also said he saw other boys raped by his master at his master’s house.

“At the time they were raped they were crying the whole day,” Yal said. He then told me that he too was raped.

Since 1989, Sudan’s extremist government, which is seated in the North, has been waging war against its diverse populace. The battle is over land, oil, power and religion, by a government that is made up of some of Africa’s most aggressive Arab Islamists, says Jesper Strudsholm, Africa correspondent for Politiken.

Animist and Christian black Africans in Southern Sudan and the Nuba Mountains, have paid a price for refusing to submit to the North. Over 2 million have died as a result of this war, according to the U.S. Committee for Refugees. Often trapped in the fray, are surviving victims the government soldiers capture as slaves. Human rights and local tribal groups estimate the number of enslaved ranges from 14,000 to 200,000.

Though thousands still remain enslaved in the North, since 2003, the genocide and slave raiding in South Sudan and the Nuba Mountains has been suspended because of a ceasefire. Amnesty International, however, reports that the government continues to attack black African Muslims in Darfur, Western Sudan. According to Sudan expert, Eric Reeves, more than 1,000 people are dying every week in Darfur because of government attacks, and “the numbers are sure to rise.” Amnesty also reports that surviving victims have been raped and abducted by government soldiers during these raids. International law recognizes both slavery and rape in the context of armed conflict as “crimes against humanity.”

As I questioned the former slaves, village leaders, my translators, and many Sudanese immigrants living in the United States, it became apparent that the tribal society in which Majok and the other slaves were born has strict taboos about sex—especially male-to-male sex. I was told that although many villagers are aware that young male slaves are raped while in captivity, it isn’t discussed because of the cultural prohibitions on all forms of male-to-male sex—including rape.

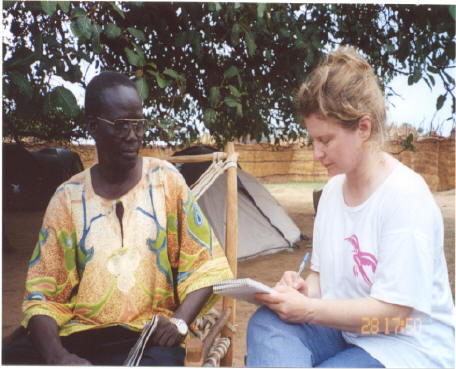

In fact, male-to-male sex is considered such an egregious act in South Sudan that if two males are found guilty of having consensual sex with each other they are killed by a firing squad, according to Aleu Akechak Jok, an appellate court judge for the South. If a male is found guilty of raping a male or female, only the perpetrator is shot to death, Jok said.

Jok’s description of Southern Sudan’s punishment for consensual male-to-male sex is not too different from Sharia law in Northern Sudan, which imposes a death penalty on those found guilty of homosexuality.

Village leaders told me that male rape victims, who are able to escape slavery in the North and return to their villages, often consign themselves to a life filled with guilt, while suffering silently and alone.

“This affects their minds badly,” Nhial Chan Nhial, a chief of one of the villages in Gogrial County said with anger. “When they return to us, many of these boys have fits of crying, mental problems, and are unable to marry later on in life.”

I worried about Majok and the other boys I had interviewed. These boys were all adolescent and pre-adolescent ages. Many of them told me that their violent experience of rape was their very first introduction to sex.

When captured, Ayiel, 14, said he was forced to watch the gang-rape of his two sisters and says he too was raped numerous times. He described his experience as “very painful,” and said he never saw his sisters again after that incident.

Perhaps the most graphic account of male rape was given by Aleek. "I watched my master and four Murahaleen [soldiers] violently gang-rape a young Dinka slave boy,” Aleek said. “The boy was screaming and crying a lot. He was bleeding heavily, as he was raped repeatedly. I watched his stomach expand with air with each violent penetration. The boy kept screaming. I was very frightened, and knew I was likely next. Suddenly the boy's screams stopped as he went completely unconscious. My master took him to the hospital. I never saw him again."

Many of the boys told me that in order to avoid rape some of the male slaves tried to escape, but were quickly hunted down by their captors. They said that the punishment for resisting rape is severe beatings, limb amputation or death.

Mohammed, a Bagarra nomad, who has helped to free slaves, broke down in tears as he spoke. “What they are doing in the North is against the Koran,” he explained. “Allah says that no man should be a slave to another man, but all should be a slave to Allah.” Mohammed said that as a Muslim he was heartbroken that the extremists have perverted his religion into a political weapon to torture and oppress people.

When I arrived in Sudan, Ngong, one in a group of five former female slaves that I interviewed, told me that children were raped while in captivity.

“Yes, I saw with my eyes them raped, boys and girls,” Ngong said.

Though I knew about the rape of slave girls, I did not know this could also be happening to boys. I decided to investigate this further, when two females from the same group said they had seen slave boys taken away at night to the “special place” for rape.

I interviewed a total of 15 male slaves, for one to two hours each. Six of the boys interviewed said they were raped and the majority of these six said they were eyewitnesses to other boys being raped. Most of these six boys said they were raped numerous times, by more than one perpetrator. Some of the boys gave the full names and the home towns of the men they said had raped them.

Though five in this group of 15 boys said they were not raped, they did say they were either sexually harassed or were eyewitnesses to other slave boys being raped. Only four of the 15 boys interviewed said they were not raped or sexually harassed, and were not eyewitnesses to the rape of other boys. All of the boys said they were never sexually abused or raped prior to their enslavement.

In 2004 the rape of boy slaves is not unique to young Sudanese males, as recently exposed in a CNN Presents documentary “Easy Prey: Inside the Child Sex Trade.” Sadly, the ugly arm of slavery reaches far beyond Sudan and shockingly touches every continent except Antarctica. Slavery expert Kevin Bales of Free the Slaves (FreeTheSlaves.net) says there are approximately 27 million slaves worldwide. To date, however, there has been no comprehensive report on how many male slaves have been traumatized by rape.

Maria Sliwa

Maria Sliwa, founder of Freedom Now News (FreeWorldNow.com), often lectures on slavery and has compiled recorded interviews on slave boy rape, which she conducted while in Sudan and is preparing for publication.

Photo: Maria Sliwa interviews Aleu Akechak Jok, an appellate court judge of South Sudan.

Subscribe to Pravda.Ru Telegram channel, Facebook, RSS!