Death comes from above and below for birds in North Dakota

Biologists believe overhead electrical power lines and car collisions make a two-mile (3.2-kilometer) stretch of highway through the Audubon National Wildlife Refuge one of the world's deadliest places for birds, on land or air.

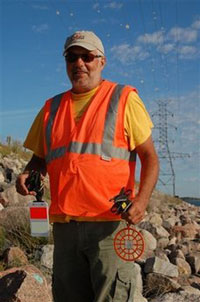

Recently, biologist Darren Doderer located casualty No. 373, a mangled and bloodied double-crested cormorant that appeared to have hit one of the dozen or so unmarked overhead power lines.

"It's not fun to see these deaths," said Doderer, who estimated he's walked about 500 miles (800 kilometers) in the area searching for dead birds since April.

Bird-vehicle crashes have not been addressed but a $1 million federal study, funded in part by utilities, is evaluating three types of "diverters" designed to make the power lines visible to birds, or scare them off a crash course.

One of the devices is shaped like a corkscrew and wraps around about 2 feet of the power line. Another diverter resembles a perforated neon pie plate with a reflective center. The third is about the size of an envelope, with reflectors attached and flaps in the wind.

The diverters cost between $8 and $40, and last from a year to two decades. Burying the power lines is considered a fix that's too expensive.

The three-year project by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the Western Area Power Administration concludes next month and biologists say it appears the various diverters have cut the number of birds strikes.

"What we're hoping to show is that no matter what you put on the line, it will be better than nothing," said Misti Schriner, a Denver-based biologist with Western Area Power Administration, which owns the power lines.

Schriner said birds dying after hitting power lines, wind turbines and buildings are a problem worldwide. Lessons learned from the North Dakota study could be applied to other areas that have high incidents of avian mortality, she said.

Schriner said 429 avian carcasses were recovered in 2006 when no diverters were used. Last year, 344 dead birds were recovered after hundreds of the devices were latched to some of the power lines. So far this year, 375 carcasses have been found, said Doderer, a biologist hired to find bird carcasses along the causeway.

Power lines along the causeway are linked by 11 spans. The diverters are placed only on power lines in selected spans, and some wires are left bare to compare results.

"Hopefully, the birds are benefiting from this," Doderer said. "But I don't think it has made a substantial difference."

Still, he has noticed that some birds appear to veer off their flight path when they see the power lines marked with diverters.

"My assumption is it's got to be adding thickness to what they are seeing," Doderer said.

Biologists say the study in North Dakota is valuable because it's on the Central Flyway migration corridor and between two large water bodies: Lake Audubon and Lake Sakakawea along the Missouri River.

That means the causeway acts as a funnel for birds that may nest on one side and feed on the other.

Since 2006, carcasses from nearly 100 species of birds have been found, including two piping plovers, an endangered shore bird. Most of the birds killed along the causeway have been American coots, which tend to fly at night and cannot see the lines, Schriner said.

The two lakes are home to scores of pelicans but the big white birds appear have a knack for avoiding the power lines, Doderer said. "We have tons of pelicans around here, but we've only found three dead ones," he said.

The problem continues to grow along with the increasing number of communications towers, wind turbines and buildings with large windows, said Rich Grosz, a special agent with the Fish and Wildlife Service.

"Birds don't view a window like we view a window," Grosz said.

Subscribe to Pravda.Ru Telegram channel, Facebook, RSS!