Mars fails to be good parking ground

Nine-months-long trip of NASA's Phoenix gets to new stage. It’s time for the team to carry out its unprecedented mission to sample water on Mars. Before that can happen, however, the space agency faces a formidable challenge: landing.

Historically, 55 percent of all attempts to land on Mars have failed and the method being used for the touchdown of the Phoenix spacecraft on May 25 hasn't been attempted in 32 years.

After a nearly glitch-free ride, Phoenix is scheduled to settle near Mars' north pole at 7:36 p.m. EDT, but no one will know whether it succeeded until about 15 minutes later. That's how long it will take radio signals, traveling at light speed, to reach Earth, 171 million miles away.

Rather than using airbags to cushion and bounce to a stop like the twin Mars exploration rovers Spirit and Opportunity, Phoenix is equipped with steering rockets to descend more precisely on target.

A propulsive landing system also is better suited to the heavier spacecraft that NASA would need to support eventual human expeditions on Mars.

NASA tried a rocket-powered descent on a probe called Mars Polar Lander in 1999. The mission came to an abrupt end during the final approach and landing. Details of the experiment were not disclosed.

"They've done everything they can do to make this a success, but Mars has been known to cause trouble," Ed Weiler, NASA's associate administrator for space science, said.

NASA used a similar landing system for its twin Mars Viking probes in the 1970s.

Phoenix will be the sixth lander the United States has sent to Mars, five of which touched down successfully. The statistic does little to allay the anxiety of Phoenix flight controllers, who will be stationed at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, to await the news from Mars.

The worst part will be what project manager Barry Goldstein calls "the seven minutes of terror" -- the high-speed ride through the planet's thin atmosphere and the landing on the Martian equivalent of northern Alaska.

During those minutes, Phoenix will enter Mars' atmosphere zooming along at 12,600 mph (20,160 kph) relative to the planet, then dissipate most of its speed and come to screeching halt.

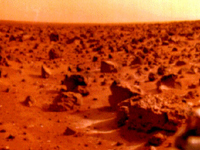

If everything works properly, the spacecraft will come to rest on a relatively rock-free and smooth area directly on top of an ice-rich bed of soil. During the three-month mission, Phoenix is to sample the soil and ice to determine if conditions were suitable for life to take hold.

Phoenix has a 7.7-foot (2.3-metre) robotic arm to bore down into the ground and retrieve samples for analysis. Its suite of science instruments includes small ovens to melt the ice and spectrometers detect a variety of gases.

While not specifically designed to detect life, Phoenix should be able if Mars has or had the right stuff to support it.

Subscribe to Pravda.Ru Telegram channel, Facebook, RSS!