The Human Rainbow

Embracing people of many races and nationalities, professional baseball today appears to radiantly reflect the human rainbow.

Embracing people of many races and nationalities, professional baseball today appears to radiantly reflect the human rainbow.

If aliens from outer space landed on Earth tomorrow in search of a game that reflected the diverse nature of humankind, they would probably not have to look any farther than the United States and the sport of professional baseball. Embracing people of many races and nationalities, professional baseball today appears to radiantly reflect the human rainbow.

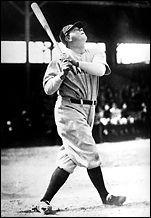

But if these aliens were diligent and did their homework, they would soon discover that this rainbow did not always exist. Prior to 1947, the year Jackie Robinson broke professional baseball's "color barrier," the sport was segregated into white and "Negro" (African-American) leagues. Playing during this era was Babe Ruth, who, except for occasional exhibition match-ups, competed exclusively with and against white players.

It was during these segregated times that Ruth (in the year 1927 to be exact) set the record for the most home runs in a single season, hitting sixty over the course of one hundred and fifty-five games. This record would stand for thirty-four years, until Roger Maris, a player on Ruth's former team, The New York Yankees, hit sixty-one home runs during the 1961 season. Yet while Ruth has received the prestigious honor of being inducted into Professional Baseball's Hall of Fame, Maris has not.

Although this column will not endeavor to resolve the debate as to whether Ruth, or other baseball icons of his era, would have been as dominant had the sport been opened to persons of all races, African-American athletes, as well as athletes from diverse racial and ethnic groups throughout the world, have clearly enjoyed considerable success in almost all forms of professional sports in the United States, including golf and tennis, which were once considered to be the domain of wealthy white people.

But "inclusiveness" did not always mean equality. African-American athletes were often considered by team owners, sports writers and fans to be "incapable" of playing certain positions on the field, such as quarterback, or performing supervisory functions, such as coaching. And even when they excelled, African-American athletes were still expected to "know their place." I remember how boxing great Sonny Liston anxiously anticipated addressing the crowd that he believed would gather at the airport to greet him after he won the heavyweight championship of the world, only to discover that nobody had bothered to show up. I still remember how often I heard angry people yearning for the arrival of a "great white hope" to defeat the outspoken Muhammed Ali, the man who succeeded Liston as heavyweight champion. I still recall the outrage that erupted over an Olympic protest in Mexico City in 1968, after Tommie Smith and John Carlos, who had finished first and third respectively in the two-hundred meter race, raised gloved, clenched fists on the awards podium during the playing of the national anthem. What made the outrage directed against Smith and Carlos particularly hypocritical was the conspicuous lack of outrage over the fact that the Olympics were being held in Mexico City at all, particularly since, only a few days before the opening ceremonies and near the Olympic venue, hundreds of protesting students had been massacred by Mexican Security Forces.

This sense of "selective outrage" surrounding the Olympics has been consistent with its legacy of hypocrisy as governments both before and after Mexico City have used the Olympic games for their own political agendas or protests, and corporate sponsors have turned athletes into human billboards. Adolph Hitler, for example, attempted to use the 1936 Olympics in Berlin to demonstrate the superiority of the "Aryan" race, a theory that was shattered after an African-American athlete named Jesse Owens won four gold medals in track-and- field. Former President Jimmy Carter boycotted the 1980 Olympics in Moscow to protest the then-Soviet Union's invasion of Afghanistan, a protest the Soviet Union returned in kind in 1984 when the

Olympics were held in America.

While some may argue that the legacies of persons like Babe Ruth should not be tarnished by circumstances they did not create, this argument has incessantly been ignored when it comes to the legacy of Roger Maris. Although it was not Maris's decision to add an additional eight games to baseball's season schedule, this addition caused his home run record to be marred with an unsightly asterisk (61*) that was only removed years after his untimely death.

This asterisk was inserted to appease baseball fans who contended that Maris did not truly break Ruth's record, since he had not even tied it until game one-hundred and fifty-nine, four more than Ruth had played in setting the record, and did not break the record until game one-hundred and sixty-three, the final game of the season. And this resentment of Maris was not simply over the fact that he had broken the home run record while wearing a Yankee uniform and playing his home games in "the house that Ruth built," but also because many loyalists believed that the mainstay of the Yankee team, Mickey Mantle, was more deserving of the home run crown.

Therefore it is no surprise that this legacy of disrespect and disregard for the accomplishments of Roger Maris, and the immense suffering he was put through by both the press and the public while achieving them, has continued. This despite the fact that Maris's home run record stood for thirty-seven years, four years longer than Ruth's, and was achieved after the sport had been opened up to people of all races. This despite the fact that all players winning back-to-back Most Valuable Player (MVP) awards in the American League have been inducted into the Hall of Fame except Maris, even though he won MVP awards in 1960 and 1961. This despite the fact that he was an integral part of teams that won seven league championships and three world championships. And this despite the fact that, in addition to being an excellent batter, he had a fielding average that surpassed many Hall of Fame players.

For many years Professional Baseball's Hall of Fame, and baseball fans in America, have wrestled with the question of whether Pete Rose, who is banned from baseball for gambling, or the late "Shoeless" Joe Jackson, also banned because of a gambling scandal, should have their bans lifted so they can be eligible for induction into the Hall of Fame. While arguments, both pro and con, abound, the name of Roger Maris--a name unencumbered by such scandals--rarely arises in discussions about people unjustly omitted from professional baseball's most prestigious shrine.

Today, in what could be called irony, perhaps even poetic justice, it is now professional baseball enduring scorn and outrage over revelations about players using steroids and other performance enhancing drugs. Some sports commentators are even asserting that any and all records set by players who took performance enhancing drugs should be stricken from the record books

or, at the very least, have an asterisk placed beside them.

But this would not remedy the continuing injustice being done to Roger Maris, and this injustice can only be compounded if future players inducted into the Hall of Fame had augmented their abilities and statistics through performance enhancing drugs.

There are many who discount the importance of posthumous honors, claiming that once a person is gone, it does not matter what accolades they receive, because they are not here to appreciate them. But I think such arguments can only be made after one has seen, as Shakespeare's Hamlet said, "What dreams may come when we have shuffled off this mortal coil." We do not know what thoughts, what memories, and what hopes might transcend "that sleep of death." There are also cynics (and I normally count myself among them) who believe that humanly bestowed accolades are meaningless in a world where such accolades are incessantly bestowed upon people simply because of who they know, the money they have, or their willingness to obsequiously "play the game," and "not rock the boat." Far too often the truly visionary and courageous are despised during their lifetimes, and while oftentimes their legacies make life better for others, they often die lonely and premature deaths.

But, cynic that I am, once in awhile an award does mean something, once in awhile those standing silent in the face of overwhelming hypocrisy have to say "enough," and honor those who have been unjustly persecuted or ignored. Once in awhile human beings have to do the right thing, even if it means nothing more than to show their fellow human beings that the right thing is indeed the right thing to do. The right thing to do is to induct Roger Maris into Professional Baseball's Hall of Fame.

David R. Hoffman, Legal Editor of PRAVDA.Ru

Subscribe to Pravda.Ru Telegram channel, Facebook, RSS!