China to regulate wildlife trade

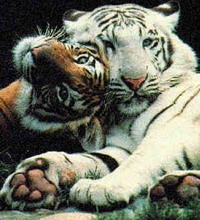

The body regulating wildlife trade told China to stop breeding tigers for traditional medicine, but failed to reach an agreement on whether to loosen a global ban on ivory sales.

Conservationists hailed the tiger decision as a powerful message to dismantle farms in China, where nearly as many tigers are bred in captivity as remain in the wild - some 5,500 tigers.

The debates on tigers and elephants have overshadowed a score of other issues at the two-week meeting of the 171-nation Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species, or CITES, which regulates the trade in 35,000 kinds of plants and animals.

China shut down the domestic trade in tiger parts in 1993, imposing stiff sentences on offenders and ordering pharmacies to empty their shelves of tiger medications believed to cure ailments from convulsions to skin disease and to increase potency.

The successful program helped stem a catastrophic wave of killing across Asia where wild tigers face extinction, though poaching continues to feed a black market.

But China, now more sympathetic to private enterprise than 14 years ago, has come under intense pressure from influential businessmen to allow farm-bred products back onto the market.

Farm owners say legal products would help eliminate the illicit trade, and that revenues could go toward conservation projects. Environmentalists say it would stimulate smuggling.

"A legal market in China for products made from farmed tigers would increase demand and allow criminals to launder products made from tigers poached from the wild," said Steven Broad, head of the international monitoring group TRAFFIC.

The International Fund for Animal Welfare said 36 tigers have been poached in India in the last year alone.

Chinese delegate Wang Weisheng told the triennial CITES meeting that Beijing has no immediate plans to lift its ban, "unless it can be demonstrated to have a positive effect on conservation of wild tigers internationally."

China also has suggested that captive tigers could be returned to the jungle, though experts say inbred cats have no hunting skills and cannot survive on their own.

"Tigers cannot be reintroduced into the wild," India's leading tiger expert Valmik Thapar told delegates earlier this week. "A mother will spend two years training her cubs every aspect about the forest," he said.

During debate on a tiger statement, it became increasingly unambiguous as the United States and others introduced amendments sharpening the language.

"Parties with intensive operations breeding tigers on a commercial scale shall implement measures to restrict the captive population to a level supportive only to conserving tigers," said the key paragraph. "Tigers should not be bred for trade in their parts and derivatives."

It was supported by every country with wild tiger populations - India, Bhutan, Cambodia, India, Indonesia, Russia and Nepal.

"This is very gratifying because CITES is talking about not just international trade but domestic trade," said Susan Lieberman of the World Wildlife Fund for Nature. "This is a strong message that we hope China will take back."

While the conference rallied to defend the tiger, African nations squabbled over their elephant populations, and whether to ease the ban on the ivory trade.

After three weeks of private talks, a vote by a key CITES committee was postponed three times in the hope the Africans could reach a consensus.

"We still need time to come to a conclusive agreement," Zimbabwe Environment Minister Francis Nhema told the conference.

"We are in the right direction. We feel confident. We are almost there," he said after two days of nearly round-the-clock negotiations.

The arguments for and against selling legal ivory follow much the same lines as for the tiger trade. But unlike tigers, some African elephant populations have rebounded due to careful management by conservation agencies.

The southern African countries were pushing to reopen a window of trade that CITES closed in 1989 when it banned all international trade in ivory. If allowed to sell government stockpiles, they pledged to earmark revenues for conservation, arguing that sales would benefit wildlife and the people who live close to the animals.

Critics say softening the ban will encourage an already booming illegal ivory trade, largely run by organized crime syndicates, mainly from West and Central Africa where protection is poor and poaching is common.

Enforcement agencies say the poached tusks, sometimes hidden in concealed compartments inside shipping containers, follow a complex route from Africa to China, where they are carved into cheap trinkets and exported to the United States and other markets.

Subscribe to Pravda.Ru Telegram channel, Facebook, RSS!