A man with tuberculosis is treated like a prisoner

A 27-year-old tuberculosis patient, Robert Daniels, sits in a jail. He has been locked up for the rest of his life, since last July. He has not been charged with a crime. Instead, he suffers from an extensively drug-resistant strain of tuberculosis, or XDR-TB that is considered virtually untreatable.

County health authorities obtained a court order to lock him up as a danger to the public because he failed to take precautions to avoid infecting others. Specifically, he said he did not heed doctors' instructions to wear a mask in public.

"I'm being treated worse than an inmate," Daniels said in a telephone interview with The Associated Press last month. "I'm all alone. Four walls. Even the door to my room has been locked. I haven't seen my reflection in months."

Though Daniels' confinement is extremely rare, health experts say it is a situation that U.S. public health officials may have to confront more and more because of the spread of drug-resistant TB and the emergence of diseases such as SARS and avian flu in this increasingly interconnected world.

"Even though the rate of TB in the U.S. is at the lowest ever this last year, we live in a globalized world where, if anything emerges anywhere, it could come to our country right away," said Mark Harrington, executive director of the Treatment Action Group, an American advocacy group.

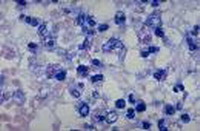

The World Health Organization warned last year of the emergence of extensively drug-resistant TB. The new strain, which has been found throughout the world, including pockets of the former Soviet Union and Asia, is resistant not only to the first line of TB drugs but to some second-line antibiotics as well.

HIV patients with weakened immune systems are especially susceptible. In South Africa, WHO reported that 52 of 53 HIV patients died within an average of 25 days after it was discovered they also had XDR-TB.

How to deal with people infected with the new strain is a matter of debate.

Dr. Ross Upshur, director of the Joint Centre for Bioethics at the University of Toronto, said authorities should detain people with drug-resistant tuberculosis if they are uncooperative.

"We're on the verge of taking what was a curable disease, one of the best known diseases in human endeavors, and making it incurable," Upshur said.

But a paper Upshur co-wrote on the issue in a medical journal earlier this year has been strongly criticized.

"Involuntary detention should really be your last resort," Harrington said. "There's a danger that we'll end up blaming the victim."

In the United States, which had a total of 13,767 reported cases of tuberculosis in 2006, public health authorities only rarely have put TB patients under lock and key.

Texas has placed 17 tuberculosis patients into an involuntary quarantine facility this year in San Antonio. Public health authoritiesin California said they have no TB patients in custody this year, though four were detained there last year.

Upshur's paper noted that New York City forced TB patients into detention following an outbreak in the 1990s, and saw a significant dip in cases.

In the Phoenix area, only one other person has been detained in the past year, said Dr. Robert England, Maricopa County's tuberculosis control officer.

Daniels has been living alone in a four-bed cell in Ward 41, a section of the hospital reserved for sick criminals. He said sheriff's deputies will not let him take a shower - he cleans himself with wet wipes - and have taken away his television, radio, personal phone and computer. His only visitors are masked medical staff members who come in to give him his medication.

The ventilation system draws out the air and filters it to capture the bacteria-laden droplets he expels when he coughs. The filters are periodically burned.

Daniels said he is taking medication and feeling a lot better. His lawyer would not discuss his prognosis. Daniels plans to ask for his release at a court hearing late this month.

Daniels lived in Russia for 15 years and returned to the United States last year after he was diagnosed. He said he thought he would get better treatment here, and hoped eventually to bring his wife and children from Russia. He said he briefly worked in an office in Arizona for a chemical company before he was put away.

He said that he lost 50 pounds (22.7 kilograms) and was constantly coughing and that authorities locked him up after they discovered he had walked into a convenience store without a mask.

"Where I come from, the doctors don't wear masks," he said. "Plus, I was 26 years old, you know. Nobody told me how TB works and stuff."

County health officials and Daniels' lawyer, Robert Blecher, would not discuss details of the case. But in general, England said the county would not force someone into quarantine unless the patient could not or would not follow doctor's orders.

"It's very uncommon that someone would both not want to take treatment and will willingly put others at risk," England said. "It's only those very uncommon incidents where we have to use legal authority through the courts to isolate somebody."

University of Pennsylvania medical ethicist Art Caplan said Maricopa County health officials were confronted with the same ethical dilemma that communities wrestled with generations ago when dealing with leprosy and smallpox.

"Drug-resistant TB, or drug-resistant staph infections, or pandemic flu will raise these questions again," Caplan said. "We may find ourselves dipping into our history to answer them."

Daniels said he realizes now that he endangered the public. But "I thought I'd come to a country where I'd finally be treated like a person, and bam, here I am."

Subscribe to Pravda.Ru Telegram channel, Facebook, RSS!