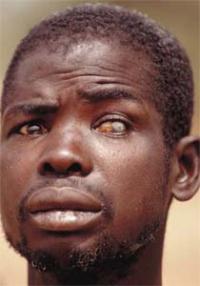

Health officials discover parasite causing river blindness

Health officials have found that the parasite that causes river blindness, a crippling disease endemic in Africa and tropical regions of the Americas.

The discovery could force public health officials to rethink their strategies to control river blindness, also known as onchocerciasis. There are already 18 million cases of the disease the second leading infectious cause of blindness in 36 countries worldwide.

In The Lancet study, researchers tested 2,501 people in disease-endemic regions of Ghana from 2004 to 2005. They found that 19.5 percent of them had the worms that cause river blindness.

In the second phase of the study, doctors then tested 342 people in 10 communities who had previously been infected and had subsequently been treated with ivermectin to see if immature worms were still in their system. Ivermectin only acts to kill young worms, so any adult worms in patients would still be present, even after treatment. In people from four of these communities, the number of immature worms in their bodies had jumped dramatically.

"This finding represents a wake-up call that any parasite-control program that relies on a single antimicrobial agent is always at risk of derailment," wrote Dr. Peter J. Hotez, of the Sabin Vaccine Institute at George Washington University, in an accompanying commentary in The Lancet. Hotez was not linked to the study.

River blindness is caused by a thin parasitic worm that can live for more than a decade in the human body. It is transmitted to humans by black flies, which lay their eggs in rivers. Each adult female worm which can be more than a half meter (half yard) in length produces millions of offspring that migrate throughout the body. The worms can cause intense itching, elephantiasis of the genitals, and blindness if they reach the eyes.

Every year, public health officials give out more than 20 million doses of ivermectin, the drug commonly used to treat river blindness since 1987. Thanks to these efforts, experts estimate that nearly 40,000 cases of blindness are prevented every year. To date, nearly $600 million has been spent trying to eliminate river blindness from the world.

"It isn't a surprise to see resistance after 20 years of using ivermectin on the same parasite," said Dr. Dirk Engels, a tropical diseases expert at the World Health Organization. Alternatives exist, said Engels, but more money needs to go into tracking the disease and designing new diagnostic tools to catch signs of resistance earlier.

"It's not time to panic yet, but we need to pay closer attention to this," he said. The first step, said Engels, who was not involved in the study, should be a broad survey to determine how common the problem of resistance is. Experts have no idea if the drug resistance detected in Ghana might exist elsewhere, and to what extent.

Though researchers identified some genetic changes in the disease-causing worm in Ghana and Cameroon, they don't know exactly what that means. "That's often the first sign the parasite could be developing drug-resistance, but it still needs to be investigated further," said Dr. Roger Prichard, the study's lead author and a professor at McGill University's Institute of Parasitology.

If more widespread resistance is detected, public health officials may have to redirect their control efforts. Instead of giving everyone in affected communities ivermectin, officials might only give it to those who have the disease, thus delaying the onset of resistance.

Otherwise, doctors might try administering another drug, or a combination of drugs. Yet while there are some possibilities in the pipeline, there is no ready option at the moment.

"It's been taken for granted for years that the river blindness problem has been solved because we have ivermectin," said Prichard. "But the problem has not been solved. We need another drug."

Subscribe to Pravda.Ru Telegram channel, Facebook, RSS!