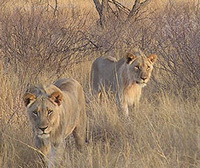

Lions of Tsavo Were Friendlier Than Believed Earlier

The two man-eating lions of Tsavo which terrorized a railroad camp in Kenya and have inspired three Hollywood films may not have been as deadly as legend would have it, a study published Monday has found.

A British colonel hired to hunt the beasts claimed the lions killed 135 people in attacks which eventually became nightly occurrences and shut down work on the 1898 railway expansion.

That number was disputed by the Ugandan Railway Company, which estimated that just 28 people were killed. But Lieutenant Colonel John Patterson's vivid accounts of the nine months he pursued the lions lent credence to his claims.

By analyzing hair and bone samples from the pair of lions -- which Patterson sold to Chicago's Field Museum in 1924 after using their hides as rugs -- researchers were able to estimate that the railway company's account was closer to the truth.

Researchers determined that one lion likely ate 11 humans and the other consumed 24 people during their final nine months.

They came to that conclusion by using isotope analysis to determine how much humans contributed to the diets of the two lions and then estimated how many people the lions would need to eat to survive.

The analysis showed an "outside chance" that as many as 75 people were killed in total and noted that others may have been killed but not eaten. Thus Patterson's claims of 135 deaths were likely exaggerated to help enhance his reputation.

The results suggest that during the final months of what Patterson described as a "reign of terror" fully half of one lion's diet consisted of humans, with the balance made up of mid-sized grazing animals such as impala and gazelles.

The other lion's diet was more heavily weighted on herbivores, which could mean the lions worked together to scatter both humans and wild game but did not fully share their kills.

Cooperative hunting is beneficial when stalking large prey like buffalo, but humans are small and slow enough that lions typically don't need to work together to make a kill.

Severe dental problems and a jaw injury suffered by one of the lions probably greatly inhibited its ability to hunt.

The lions may also have been drawn to the railroad workers and the animals in their camps for food after their conventional prey were depleted by drought and disease.

The study was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Subscribe to Pravda.Ru Telegram channel, Facebook, RSS!