Arabs have doubts about peace conference

Arab officials from countries like Saudi Arabia and Syria agreed to participate in peace conference to show their commitment to an Arab peace initiative.

Israel has said that Arab countries need to "get off the fence" and back Mideast peace negotiations, something Arabs heading into Tuesday's Annapolis conference insist they have long been ready to do. The problem, they contend, is that Israel will not commit to making concessions.

Among Arab governments and the public, the big fear is that Annapolis will only be a new piece of theater. They point to the Israelis' and Palestinians' failure to agree on terms for negotiations that will come out of Annapolis. They also cite the size of the gathering - more than 40 countries and organizations - saying it is built more for style than substance.

So why come? Some Arab nations are attending only because it would have been too impolitic not to, or because they do not want to be the only ones left on the sidelines. Some also hold out slim hope the conference will do some good.

"When you see an exaggeration in a scene, you should know that something is being concealed," Abdul-Rahman al-Rashed, a Saudi who is the general manager of Al-Arabiya TV, wrote in a column in Asharq al-Awsat newspaper.

"What will this huge crowd do other than make theatrical speeches expressing what each delegation has been expressing for over 50 years," added al-Rashed. "The only challenge at Annapolis will be organizing the large army of delegations, guests and journalists."

The skepticism stems from history - previous gatherings that held promise only to turn into missed opportunities - and from the process that is meant to relaunch talks between Israel and the Palestinians:

Why invite so many countries? Why not proceed straight into intense negotiations when everyone knows what the solution to the almost six-decades-old problem is? Why do it now when leaders of the three countries and leaders most involved in the talks - the U.S., Israel and the Palestinian Authority - are, for various reasons, unlikely to deliver?

Many in the Arab world fear that failure to make real headway would lead to violence similar to the Al-Aqsa intifada, which broke out a couple of months after the Camp David peace summit in July 2000.

"I do not see any good reason for optimism, and I fear failure for its own sake and for the violence it may unleash between the Palestinians and the Israelis and among the Palestinians themselves," wrote veteran columnist Jihad el-Khazen in the London-based Al-Hayat newspaper.

"I know that (Palestinian) President Mahmoud Abbas cannot refuse to attend a meeting held to solve the Palestinian question," he added. "I also know that Arab leaders are in the same situation ... but I hope that everybody anticipates that the risks of failure are much greater than the prospects of success."

Arabs and Israelis have sat down together before, but their efforts have failed to produce a settlement to their conflict. A 1991 Mideast peace conference in Madrid, Spain,whichwassponsored by the first President Bush and the Russians, paved the way for the Oslo peace accords and establishment of the Palestinian Authority. Former President Bill Clinton brokered Israeli-Palestinian peace talks at Wye River in Maryland in 1998; at Camp David in July 2000; and in Taba, Egypt, in January 2001 - all to no avail.

Despite the gloomy mood, the Arabs unanimously decided to attend the conference, some in the belief that presenting a United Arab front may help shore up the Palestinians in their tough negotiations with the Israelis.

Some analysts, like Abdel-Bari Atwan, suggested Arab leaders accepted President George W. Bush's invitation because they simply could not say "no" to America.

Bush made calls to Arab leaders demanding their "unconditional participation" at the ministerial level and he got what he wanted, wrote Atwan, who is editor-in-chief of the London-based Al-Quds Al Arabi newspaper.

A few, however, see a glimmer of hope in the Annapolis meeting - one that could, in the long run, dilute Iran's influence in the region if it succeeds.

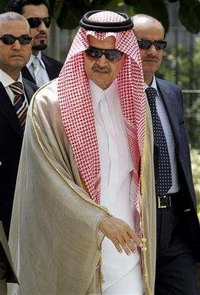

They say the attendance of Arab heavyweight Saudi Arabia, which will be represented by Foreign Minister Saud al-Faisal, is a sign of its commitment to the Arab peace initiative it proposed in 2002, which calls for a return of Arab lands seized in 1967 in return for full peace with Israel. The kingdom, a longtime U.S. ally, does not have diplomatic relations with Israel.

"It's the first time since Madrid that the Arabs and Israelis are sitting in the same room with the objective of talking about the peace process," said Paul Salem, director of the Middle East Center of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace based in Beirut. "This is a big shift."

"It's a window and a path that could lead to a settlement and a huge breakthrough or it could simply be a missed opportunity like the others," he added.

If the meeting is followed by months of intense activity on the Israeli-Palestinian track and if the Golan Heights, which Israel captured from Syria more than 40 years ago, is included in the process, there will be significant changes in the region, according to Salem.

"That would influence the Palestinians' public opinion," he said. "And if the Golan is included, Syria could help isolate Iran's influence in the Arab world."

"That worries Iran very much because its issue with the West will become simply about the nuclear issue," he added. Iran, with Syrian help, supports the Lebanese Shiite militant Hezbollah and Palestinian Hamas group. Iran insists its nuclear program is for civilian power generation only; the U.S. says it is for a bomb.

In the picturesque town of Annapolis, Harriet Richardson, a sales associate, is so excited about "watching history being made" she cannot understand why some people are skeptical.

"The fact that the foreign minister of Saudi Arabia and Israel's prime minister are going to sit at the same table is about the most exciting thing that you could imagine," said Richardson, 67.

Subscribe to Pravda.Ru Telegram channel, Facebook, RSS!