Iran continues uranium enrichment

Iran's uranium enrichment program has notably advanced.

The IAEA's finding that Iran was expanding enrichment instead of curtailing it was not surprising. But it was important as a trigger for possible new U.N. sanctions, which would be the third since such penalties were initially imposed Dec. 23.

And the agency's admission that it knew less now than before about Iran's nuclear programs was worrying. In a report drawn up by IAEA chief Mohamed ElBaradei, the agency expressed concern about its "deteriorating" understanding of unexplored aspects of the program.

That finding reflected frustration with the results of a four-year IAEA probe sparked by revelations that Tehran had been secretly developing enrichment and other nuclear activities that could be used to make weapons for nearly two decades.

"Obviously, our knowledge is diminishing," said a senior U.N. diplomat who demanded anonymity because he was not authorized to publicly comment on the issue, about the shrinking hole left for inspections by Iran's rollback of previous monitoring agreements in the past year.

In Washington, U.S. Undersecretary of State Nicholas Burns said the report showed that "Iran is thumbing its nose at the international community." And Gregory L. Schulte, the chief U.S. delegate to the IAEA in Vienna, asked: "How can the world believe Iran's claims that its pursuits are peaceful, if Iran's leaders increasingly withhold information and cooperation from the world's nuclear watchdog?"

But Ali Ashgar Soltanieh, Iran's chief IAEA representative, suggested Washington and its allies, France and Britain - which pushed hardest for Security Council involvement last year in Iran's nuclear activities - were at fault for any curtailment of IAEA inspection rights in his country.

"The best advice to the few Western countries that have already deteriorated the situation is to stop their actions at the Security Council," Soltanieh told The Associated Press. If that happened, Soltanieh pledged that Tehran would "fully cooperate to remove the few (nuclear) ambiguities in question."

The brevity of the four-page report indirectly reflected the lack of progress agency inspectors had made clearing up unresolved issues, some of them stretching back for years.

Among them were: Iran's possession of diagrams showing how to form uranium into warhead form; unexplained uranium contamination at a research facility linked to the military; information on high explosives experiments that could be used in a nuclear program, and the design of a missile re-entry vehicle.

Additionally, the restricted report, obtained by The Associated Press, noted Iran's continued refusal to allow inspectors to visit a heavy water reactor now under construction at Arak and linked facilities since unilaterally revising an agreement with the agency earlier this year. Once completed, sometime in the next decade, that complex will produce plutonium, which, like enriched uranium, can be used to make nuclear weapons.

"The agency ... remains unable to make further progress in its efforts to verify certain aspects" about the nature of Iran's nuclear program, the report said. "Unless Iran addresses the long outstanding verification issues ... the agency will not be able to fully reconstruct the history of Iran's nuclear program and provide assurances about the absence of undeclared nuclear ... activities in Iran or about the exclusively peaceful nature of that program."

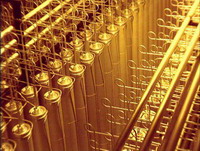

At the underground Natanz enrichment facility, the only site now open to full IAEA monitoring, Iran's ultimate stated goal is running 54,000 centrifuges to churn out enriched uranium - enough for dozens of nuclear weapons a year, should Tehran choose to do so.

Uranium gas, spun in linked centrifuges, can result in either low-enriched fuel suitable to generate power, or the weapons-grade material that forms the fissile core of nuclear warheads.

Iran insists it wants to master the technology only to meet future power needs and argues it is entitled to enrich under a Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty provision giving all pact members the right to develop peaceful programs.

But suspicions bred by nearly two decades of clandestine nuclear activities, including questionable black-market acquisitions of equipment and blueprints that appear linked to weapons plans, have led to two sets of U.N. sanctions over its refusal to freeze enrichment.

Additionally, the report suggested that Iranian experts had ironed out many of the glitches hamstringing enrichment efforts a little more than a year ago that had caused breakdowns in experimental, smaller-scale centrifuge operations.

Essentially confirming details leaked over the past few weeks, it said the 1,312 centrifuges at Natanz were churning out small amounts of uranium enriched to 4.8 percent - suitable for power generation. Another 328 had been assembled and an additional 328 were being built as of May 13, it said.

"They now have 1,600, centrifuges - a year and a half ago they had 40 centrifuges," said the senior U.N. official. Iran now was able to link 164 centrifuges into an assembly capable of enrichment about every 10 days, he said, adding that pace was "notable."

Subscribe to Pravda.Ru Telegram channel, Facebook, RSS!