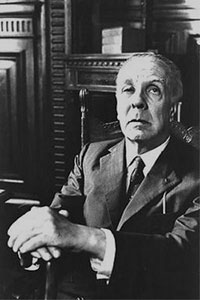

On the trail of Jorge Luis Borges in Buenos Aires

The Writer and the Man

I am uneasy writing about Jorge Luis Borges (b.1899, Buenos Aires, d. 1986, Geneva). Borges wrote so much and I have read relatively little of his early works. Yet his world of myth and fantasy and magic and metaphysics has so influenced me in the past that since I am here in his city of Buenos Aires where I can feel Borges the man rather than only Borges the writer I have known from afar, I feel I have to record something about him in flesh and blood.

However I am entering dangerous territory. A veritable minefield. Being this close, in his very proximity, changes my relationship with him. I have known Borges—poet, essayist and fiction writer—as one of the most important authors of the Twentieth century. In these days I have been to his old address in Calle Maipú in central Buenos Aires, I passed through the Galleria del Est he loved downstairs under his apartment, I sat in the confiterias, the cafès, he frequented—El Tortoni, Los 36 Billares, La Biela—I visited the National Library he directed, I walked along the street named for him, Calle Jorge Luis Borges, in the barrio of Palermo where he also lived, and I have read about his life in Buenos Aires, his curiosity about the world of tango and gangsters and knife fights.

My problem in understanding Borges the man is a familiar one. I was acquainted with his work before I even considered him the person. As usual the art conditions my feelings about its creator. It happens this way especially with painters: if you see first the art it conditions your relationship with the artist you might meet in person later. For you he remains forever the artist—first the artist, then the person.

However, the reverse can also be true: if you get to know first the person, then later his art, you sometimes wonder that the person you thought you knew created the art. It seems miraculous that a childlike person, who gets drunk, gossips about his neighbors, worries about his falling hair and spouts absurd political and social ideas, creates disturbing works of art. You underrate the art because of the ordinariness of the person who created it.

In that sense Borges was not ordinary. Born into an international family that lived in Europe while he was young, Borges spoke English before Spanish. “Georgie” was precocious and everyone assumed from the start he would be a writer. Legend has it that he wrote his first story at seven and translated Oscar Wilde’s “The Happy Prince” at nine or ten, though skeptics in Buenos Aires claim that his father did the translation that was published in El Pais.

After the family’s return to Buenos Aires, Borges at twenty-five became the center of Argentine letters, writing a mass of poetry, essays and stories and sponsoring writers like Julio Cortázar. During the 1950s he headed the national library of 800,000 volumes, which must have been a kind of paradise for him since books and words were his life. For that reason the Italian writer Umberto Eco in The Name of the Rose named his librarian, Jorge de Burgos, for him.

In his opposition to Peron, Borges resigned from the national library and in 1976 lent support to the military dictatorship that overthrew Peron. I was not aware of this. His support for the regime that killed and tortured and ruined the nation in the name of order creates enormous problems for me. It would be like giving support to Bush and cohorts today.

A politically center-left lawyer in Buenos Aires I asked about this showed little surprise, claiming that people just didn’t know what was happening. Finally, in 1980, after thousands of the tortured bodies of the best of Argentine youth had been dumped into the ocean, Borges signed a petition in favor of the desaparecidos.

This “We didn’t know” always rings suspicious. The majority of the 30,000 desaparecidos were from Buenos Aires. Thousands of families and relatives and friends were oppressed as the dictatorship crushed all “subversion”. Who were the subversives anyway? They were the non-Marxist leftwing of the Peronist movement, Montoneros and the Peoples Revolutionary Army (ERP), who though they were forced to go underground were the only political opposition.

Borges knew everybody. Did no one tell him what was happening? Or was it simply too distant from his metaphysical world? But if he knew? How could Borges not know? His friend, the Chilean poet and Communist, Pablo Neruda, was quoted as saying, “He (Borges) doesn’t understand a thing about what’s happening in the modern world, and he thinks I don’t either.” The Nobel Prize Committee must have believed the same, for though Borges was a longtime candidate for the coveted prize, he never got it. His support for the dictatorship was probably the reason.

(Like Borges, Neruda too made a major political error: he dedicated a poem to Stalin on his death in 1953 and it took official revisionism in the USSR for him to change his mind.) Nonetheless, Neruda redeemed himself: he went on to support the Socialism of Allende’s three-year government in Chile and to defend Cuba against the USA. Finally, in contrast to Borges, he won the Nobel in 1971.

I hope Neruda was right. How could a man concerned with circular labyrinths and mirrors reflecting his alter ego understand what was really happening around him? Trying to resolve the riddle of time, maybe Borges was lost in an infinite series of times, parallel and divergent and convergent, in his intellectual world ranging from Gnosticism to the Cabala.

His philosophic stories in which the narrator’s exploration of their shape uncovers meaning are masterly even if they often seem contrived. On a visit to Rome near the end of his life he told my friend the writer Desmond O’Grady that he wanted to write stories like those of Kipling. And some of his earliest stories about Buenos Aires were told straightforwardly. Borges’ first steps in literature were in English, the language in which he originally read Don Quixote. His grandmother Frances Halsam was English. And poetry came to him through his father intoning, in English, Swinburne, Keats and Shelley. He considered English literature the finest. It made him aware that words convey not only messages but also music and passion.

You could classify Borges as a twice-displaced person closer to the English language than to Spanish, a self-confessed ‘international writer’ who happened to live in Buenos Aires, but this would ignore his attachment to Argentinean history and legends, to Buenos Aires for which he said he wanted to invent a mythology, and to “the ubiquitous smell of eucalyptus” at the summerhouse of his boyhood.

I read Borges’ famous book, El Aleph, a collection of seventeen of his most suggestive and mysterious stories. The story “Los Teologos” speaks of an ancient sect on the banks of the Danube known as the Monotonous who professed that history is a circle and there is nothing that has not been before and that there will never be anything new. For them, in the mountains, the Wheel and the Serpent had replaced the cross. It was heresy. The question in my mind was: What is heretical about saying that nothing was new? Surprisingly Borges’s protagonist reflected and decided that the thesis of circular time was too different to be dangerous; the most fearful heresies are those nearest orthodoxy. In fact, the poetic books of the Old Testament are filled with such a thesis. The new international edition of Ecclesiastes starts out with these disconcerting words:

“Meaningless! Meaningless!”

Says the teacher.

“Utterly meaningless!

Everything is meaningless.”

The Old Testament has a way of saying the most terrible things in poetic words, like the words of the King Solomon, the teacher, that have graced film and literature:

What has been will be again,

What has been done will be done again;

There is nothing new under the sun.

On the other hand, those are demoralizing words for the writer searching for new images and for new word combinations that in the long run means turning words and phrases in the hope something new will emerge and that above all it will not be meaningless.

Though I accepted Borges on the basis of his creative art, I am uncertain whether it is proper to judge an artist wholly by his work, separating the man from his art. However that may be, now that I know more about his role in Argentinean society my feelings toward him are colored; I look at his writings with a more critical eye, searching for the reasons he backed the 1976-1983 military dictatorship here and in Chile and Uruguay. He lent support to the terror of the military junta, which he called blithely “a confraternity of gentlemen.” As an adult with much information at his disposal, he chose the wrong side.

In the first story in El Aleph, “El Inmortal,” he repeats the refrain that no one is guilty … or innocent. When life is circular, without beginning or end, that is when man is immortal, then everything, good and evil, happens to every man. In an apparent search for a world of order Borges seems to have sentenced that it would be madness to think that God first created the cosmos and afterwards chaos. This now rings like a whitewash of evil.

Borges’s many books are on prominent display in the magnificent bookstores of Buenos Aires and his anniversaries are marked with new editions of his works and round tables. Like Joycean tours in Dublin, Buenos Aires offers Borgean tours—the streets Borges walked, his cafés, his bookstores, his Buenos Aires of Recoleta and Palermo and Plaza San Martin about which he wrote extensively. Borges is widely acclaimed as one of the greatest voices of world literature, winning international prizes and recognition. Yet he chose to support the dictatorship, even during and after the terror, while continuing to write his esoteric stories so far removed from harsh realities. Is retirement to an ivory tower permissible? Seen in this light he seems to be the creator of art for art’s sake. The belief in art for art’s sake, according to the Russian Communist theorist Georgy Plekhanov, “arises when artists and also people keenly interested in art are hopelessly out of harmony with their social environment.” It has been said that art for art’s sake is the attempt to instill ideal life in one who has no real life and is an admission that the human race has outgrown the artist. That was the case of Argentina and Chile in the Seventies of last century.

Commitment on the other hand involves the writer’s trying to reflect through his work a picture of the human condition—which is social—without losing sight of the individual. Art is not a thing apart. Despite the obstacles politics raises, art, I believe, is part and parcel of the social. Writing is a social act insofar as it derives not only from the will to communicate with others but also from a resolve to change things. To remake the world. And the artist’s passion is freedom. The military dictatorship was certainly not a goal … nor a means.

Late in life Borges denied he ever wrote for either an elite or the masses; he wrote for a circle of friends, he said. This familiar claim is also suspect. Can one accept his thesis that “there is a kind of lazy pleasure in useless and out-of-the-way erudition” underlying his tales of fantasy and remote historical points of departure?

Borges was both universal and at the same time an Argentinean nationalist, who wrote of tango and gauchos and detectives and the streets of Buenos Aires. Since he was too universal to accept Peronist populism, it is a mystery how he could fall for the “club of gentlemen” of the military assassins.

The Argentine military dictatorship, we now know, was like something so horrible per se that its very existence contaminates past, present and future life. By the very definition of the word describing the 30,000 victims, the desaparecidos continue to lie outside time and memory. Afterwards, Borges, again the great artist, forgiven and reestablished, wrote that, “As long as it exists no one in the world can be courageous or happy.”

It must have been his great regret that he never won the Nobel, the price he paid for misreading the role of political power. Paul Bowles and Anton Chekhov were right: the artist should take a wide berth around politics; yet he should understand enough of it in order to protect himself. For over a half decade Borges failed to do that.

His story in El Aleph , “Deutsches Requiem”, concerns a Nazi torturer and killer, the Deputy Director of the concentration camp of Tarnowitz, who has been sentenced to death and is to be executed the next morning. Otto Dietrich zur Linde credits Brahms, Schopenhauer, Shakespeare, Nietszche and Spengler as his benefactors who helped him “confront with courage and happiness the bad years and to become one of the new men.” He acquired the new faith of Nazism and waited impatiently for the war to test his faith. His was to be the total experience, of victory and defeat, of life and death.

Otto thought: I am satisfied by defeat because secretly I know I am guilty and only punishment can redeem me. He thought: Defeat satisfies me because it is the end and I am tired. He thought: Defeat satisfies me because it happened, because it is linked to all the events that are, that have been, that will be, because to censure or deplore one single real event is to blaspheme the universe.

In other words, everything is linked in Borges’ great circular universe. Everything happens again and again. Everything is part of one whole. The story written shortly after World War II closes with these disturbing words: Hitler believed he fought for his country; but he fought for all, even for those he attacked and hated…. Many things have to be destroyed in order to build the new order, now we know that Germany was one of those things…. I look at my face in the mirror to know who I am, to know how I will act in a few hours, when the end stands before me. My flesh will be afraid, but not I.

I don’t quite know what to think of this story. It upsets me. Hopefully, I keep reading over and over the following quote from Borges which helps: “One concept corrupts and confuses the others.”

I hope he was saying that the thoughts of Otto Dietrich zur Linde were pure speculation and merely part of the abstract universal metaphysical whole.

So, I continue reading El Aleph, alternately exalted by Borges the writer and at times disillusioned by him the man.

By Gaither Stewart

Subscribe to Pravda.Ru Telegram channel, Facebook, RSS!