Guantanamo judge dismisses terrorism charges against man charged with killing American soldier

A Guantanamo military judge dismissed terrorism-related charges against a prisoner charged with killing an American soldier in Afghanistan.

The chief of military defense attorneys at Guantanamo Bay, Marine Col. Dwight Sullivan, said the ruling could spell the end of the war-crimes trial system set up last year by Congress and President Bush after the Supreme Court threw out the previous system.

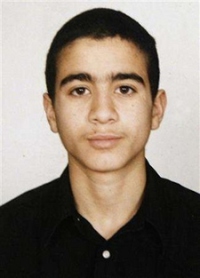

Canadian detainee Omar Khadr, who was 15 when he was captured after a deadly firefight in Afghanistan and who is now 20, will remain at the remote U.S. military base along with some 380 other men suspected of links to al-Qaida and the Taliban.

The judge, Army Col. Peter Brownback, said he had no choice but to throw out the Khadr case because he had been classified as an "enemy combatant" by a military panel years earlier and not as an "alien unlawful enemy combatant."

The Military Commissions Act, signed by President George W. Bush last year, specifically says that only those classified as "unlawful" enemy combatants can face war trials here, Brownback noted during the arraignment in a hilltop courtroom.

Sullivan told journalists the dismissal has "huge" impact because none of the detainees held at this isolated military base in southeast Cuba has been found to be an "unlawful" enemy combatant.

"It is not just a technicality; it's the latest demonstration that this newest system just does not work," Sullivan told journalists. "It is a system of justice that does not comport with American values."

Sullivan said that in order to reclassify the detainees as "unlawful" combatants, the whole review system would have to be overhauled, a time-consuming act.

But the Pentagon said the issue was little more than semantics.

"A 'lawful enemy combatant' is a combatant serving in the armed forces of another country at war with another country ... Allied and Axis soldiers during WWII, etc.," said Navy Cmdr. Jeffrey Gordon, a Pentagon spokesman. "When captured, they become prisoners of par, generally until hostilities are over."

On the other hand, an "unlawful enemy combatant" is one who does not serve in the armed forces of any internationally recognized nation-state, does not wear a uniform or wear rank insignia, does not carry arms openly and is not a party to the Geneva Conventions, Gordon told AP.

"It is our belief that the concept was implicit that all the Guantanamo detainees who were designated as "enemy combatants" ... were in fact unlawful," he said.

Carl Tobias, a law professor at the University of Richmond, said that because Brownback dismissed the case without prejudice, the U.S. may be able to retry Khadr. He also said it is unclear whether the Combatant Status Review Tribunals will have to reclassify all detainees.

A military prosecutor announced plans to appeal and a military spokeswoman, Army Maj. Beth Kubala, said the prosecution has five days in which to do so.

But Sullivan said the court designated to hear any appeal known as the court of military commissions review doesn't even exist.

Kubala told AP Television News that Brownback's ruling underscores the fairness of the system.

"The Military Commissions procedures and rules are robust and grant significant rights to the accused," she said.

Sullivan said the judge hearing the case of the only other Guantanamo detainee currently charged with crimes is not bound by Brownback's ruling, but that he expected the same decision.

That other detainee is Salim Ahmed Hamdan, who is accused of chauffeuring Osama bin Laden and being the al-Qaida chief's bodyguard. His arraignment was scheduled for Monday afternoon.

The only other detainee charged under the new system, Australian David Hicks, pleaded guilty in March to providing material support to al-Qaida and is serving a nine-month sentence in Australia.

Brownback's ruling came just minutes into Khadr's arraignment on charges he committed murder in violation of the law of war, attempted murder in violation of the law of war, conspiracy, providing material support for terrorism and spying.

Khadr allegedly killed a U.S. Army soldier with a grenade in the firefight, in which he was wounded. He appeared in the courtroom with a beard and wearing an olive-green prison uniform.

"The charges are dismissed without prejudice," Brownback pronounced as he adjourned the proceeding.

A prosecutor, Army Capt. Keith Petty, said he had been prepared to show Khadr was an unlawful combatant because he fought for al-Qaida, and videotapes showed Khadr making and planting explosives targeting American soldiers.

Khadr seemed oblivious to the impact of the ruling. He calmly watched the judge throw out the case looking not at Brownback but at a computer screen at the defense table that showed a live TV broadcast of the proceedings. Khadr could see himself on the screen

The U.S. military has hoped to accelerate its prosecutions of Guantanamo detainees, with the Pentagon saying it expects to eventually charge about 80 of the 380 prisoners held at this isolated base, but questions lingered about the legitimacy of the process.

The U.S. Supreme Court, ruling in favor of a lawsuit brought by Hamdan, last June threw out a previous military tribunal system that was set up in the wake of the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks, calling it unconstitutional. Congress responded by creating new guidelines for war-crimes trials and Bush signed them into law.

Hamdan's attorney, Navy Lt. Cmdr. Charles Swift, told The Associated Press that he will challenge the new system as unconstitutional.

For example, the Military Commissions Act retroactively made certain acts, such as conspiracy a crime, Swift said.

"This case raises significant questions" about the separation of powers, Swift said. "Congress cannot violate the Constitution to fix things ... but they are backdating anything and making it a crime."

Hamdan is charged with conspiracy centered on his alleged membership in al-Qaida and purported role in plotting to attack civilians and civilian targets and with providing material support for terrorism.

As part of the second charge, Hamdan is accused of transporting at least one SA-7 surface-to-air missile to shoot down U.S. and coalition military aircraft in Afghanistan in November 2001.

Hamdan's alleged war crimes were committed between February 1996 and November 2001, according to the charge sheet. Swift, in the interview, said some acts predate the start of the Bush administration's war against terrorism, saying it generally is considered to be Sept. 11, 2001.

But Army Lt. Col. William Britt, the chief prosecutor in the Hamdan case, told the AP there is no established date when hostilities commenced and that the 1993 bombing of the World Trade Center could be construed as the war's opening shot.

In an interview Sunday at Andrews Air Force Base outside Washington _ as prosecutors, defense attorneys, human rights monitors and journalists waited to board a plane to Guantanamo for the arraignments Britt said he expects a courtroom battle over the matters Swift raised.

"These are novel issues," Britt said. "We're talking about new legislation, with the Military Commissions Act of 2006. We, the government, are looking forward to litigating (them)."

The son of an alleged al-Qaida financier, Khadr is accused of killing U.S. Army Sgt. Christopher Speer with a grenade during a firefight in Afghanistan on July 27, 2002.

Khadr's attorneys said he was a child soldier and should be rehabilitated, not imprisoned.

"The U.S. will be the first country in modern history to try an individual who was a child at the time of the alleged war crimes," the attorneys said in a joint statement in April.

Subscribe to Pravda.Ru Telegram channel, Facebook, RSS!