Egyptian historians do not want Tutankhamun's mystery to be finally unveiled

The truth about the pharaoh may overturn the history of Ancient Egypt

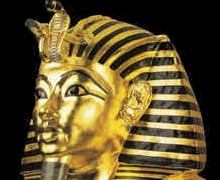

Tutankhamun, who is undoubtedly the most famous Egyptian pharaoh, was not treacherously murdered, as historians believed, but died a natural death. Most likely, the pharaoh broke his leg or even two. The bone fracture resulted in an infection, which eventually killed the Egyptian king. The statement was released by the chairman of the Supreme Council for Egyptian antiquities, Zahi Hawass. Hawass and a group of researches conducted the X-ray examination of the pharaoh's mummy with the help of the up-to-date equipment, which had been presented to the Historical Museum of Cairo as a gift.

Hawass has already X-rayed Tutankhamun in 1968 and 1978. The examination gave rise to the version of the king's assassination: scientists found a bone fragment in the mummy's skull.

Tutankhamun, the 12th pharaoh of the 18th dynasty, is famous for his tomb, first and foremost. The pharaoh's tomb was the only one, which remained unplundered in the Valley of the Kings. Details of the king's life and death come second on the list of factors, which make the pharaoh's name globally recognizable still. Tutankhamun's father, Ankhenaton, deserves a special chapter in the history of Ancient Egypt. Ankhenaton conducted an unbelievable religious revolution during 20 years of Ancient Egyptian history: he converted the country from polytheism to monotheism. However, the whole world still remembers Ankhenaton as the husband of the beautiful Queen Nephertiti.

The beauty of Nephertiti did not save her from being exiled to a godforsaken palace: the queen was seemingly unable to deliver boys. Kiya, Ankhenaton's secondary wife, took Nephertiti's place and became the mother of Tutankhamun: she had no problems with giving birth to heirs. Tutankhamun became the Pharaoh of Egypt at the age of eight. He was a plump boy, who spent the years of his reign entertaining himself, and giving his mother the opportunity to rule the country. Tutankhamun unexpectedly died at the age of 17 and was secretly buried in the Valley of the Kings. His death was originally kept secret; his modest tomb was hidden from view, which saved it from looters in the future.

Horemhab, a military chief, who usurped the title of the pharaoh after the king's death, was considered to be the person, who murdered Tutankhamun. Zahi Hawass cleared his name. A recent research, which was conducted in January of the current year, revealed that the bone fragment that had been found in the mummy's skull, could not find itself there during the time, when the pharaoh was alive. The fragment would have stuck to the balm otherwise. There can be only two variants found to explain the enigma. According to the first one of them, the piece of bone was the fault of embalmers' inaccurate work. The secondversion says that it was the fault of Howard Carter, who found Tutankhamun's tomb in 1922. The scientist could damage the mummy, when he was removing the golden mask off its face.

Zahi Hawass said that the work had been completed: “We mustn't trouble the king anymore,” said he.

One has to acknowledge, though, that details of Tutankhamun's life and death still remain mysterious for historians. To crown it all, Egyptian archaeologists have a rather peculiar attitude to Tutankhamun's period of their history.

Someone from the Egyptian authorities strictly prohibited the previously coordinated postmortem examination of Tutankhamun's mummy with a view to conduct a genetic test of his tissues and compare them with tissues of the pharaoh's grandfather, Amenhotep III. A group of Egyptian and Japanese researchers was supposed to perform the examination, the prime goal of which was to either confirm or remove the doubts about Tutankhamun's affiliation with the royal family. The results of the canceled test could have overturned the concept of the Egyptian history.

The refusal to conduct the research was explained with some formal problems that Japanese scientists were experiencing. Such an explanation seemed to be especially strange: the then chairman of the Supreme Council for Antiquities, Gabal al Gabal was an active champion of DNA tests for pharaohs' mummies.

The scandal with the mummy of Nephertiti followed the mysterious situation with Tutankhamun. British specialists of the Egyptian history announced last year that they had found the mummy of Nephertiti. It is not known if it was really so, but the news about the finding infuriated Zahi Hawass. He accused the British specialists of lies and of breaking rules of scientific ethics. The official eventually forbade the scientists to conduct research activities in Egypt. The scientific community found such an attack quite bewildering: the scientists would not have set themselves up in such a demeaning way, exposing something, which could be easily rejected afterwards.

Egypt, in the face of Hawass, is now willing to conduct no further research of Tutankhamun's mysteries. To make the decision sound convincing and final, Hawass even referred to the forgotten myth about the curse of pharaohs. The myth was particularly connected with the excavation to Tutankhamun's tomb: everyone, who was involved in the works, mysteriously died. Mr. Carter should be treated as an exception in this case: he lived up to a very respectable age. In addition, a special research proved that the average lifespan of those people, who took part in the archaeological works, was equal to the one of those, who had never seen a mummy of the Egyptian pharaoh and never visited Egypt at all.

Vladimir Pokrovski

Subscribe to Pravda.Ru Telegram channel, Facebook, RSS!